8 Lorenz Curve Analysis for Income Inequality in Kamloops

Olivia Simms

Introduction

As wealth continues to concentrate in the upper percentile of Canadian households, economic inequality is an increasingly relevant metric for citizens and policymakers to consider. In Kamloops, one does not have to travel far from the more affluent areas of Aberdeen and Upper Sahali to find neighbourhoods where residents struggle with unemployment, housing unavailability, and other socioeconomic challenges that contribute negatively to their well-being (as my fellow authors have noted).

Perhaps the most obvious component of this disparity is income inequality. Naturally, a higher income yields more opportunity, access to goods and services, and a higher overall quality of life. However, it is not clear exactly what the optimal income distribution is. You might expect (and have no quarrel with the fact) that a neurosurgeon is able to afford a nicer house than a Starbucks barista. In addition to generational wealth, one’s income can be impacted by their level of education, where they choose to live, and what type of work they choose to pursue. The degree of income inequality that our society finds tolerable is, therefore, a question of normative economics — a matter of opinion and beyond the scope of this empirical research.

It is also worth noting that comparing incomes is just one measure of economic inequality. For example, one can easily point to disparities in inherited wealth and real estate ownership. The dubious use of stratified social connections, such as nepotism and insider trading, also merits discussion. While these are salient factors to examine, they are complex to parse out, and each deserves focused research. Given that there has been very little research whatsoever on economic inequality in the Thompson-Nicola region, this study focuses solely on income inequality.

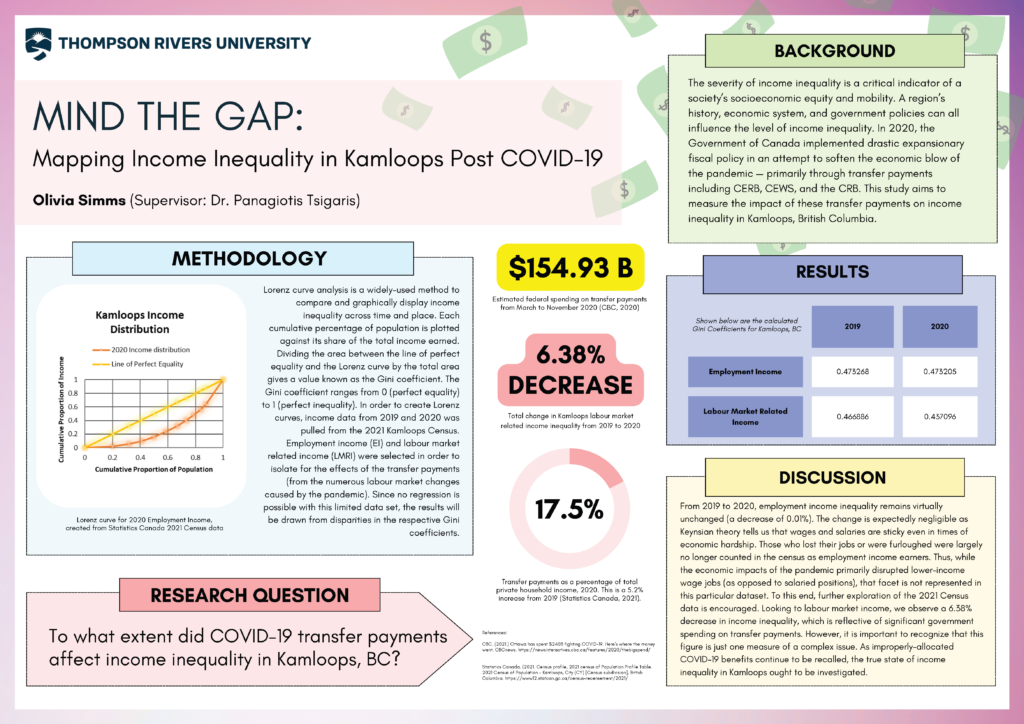

On its face, the income distribution is a function of innumerable private exchanges of labour between citizens and firms. However, the public sector is also heavily involved in the distribution of income, primarily through taxation and transfer payments. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Canada implemented a drastic expansionary fiscal policy in an attempt to soften the economic blow of shutdowns (Gatehouse, 2020). From March to November 2020 alone, the federal government spent an estimated $154.9 billion on transfer payments, such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB), Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS), and the Canada Recovery Benefit (CRB). The CERB and CRB provided direct payments to traditionally-employed and self-employed Canadians to account for lost employment income, while the CEWS was given to help businesses cover the wages of employees in the wake of shutdowns.

Given the gargantuan scope of pandemic spending, it is worth exploring the direct money-in-pocket impact this had on Canadians. To that end, this study aims to measure the effect of COVID-19 transfer payments on income inequality in Kamloops, British Columbia.

Government Transfers in Kamloops During COVID-19

The 2021 Canadian census, conducted by Statistics Canada (2023), contains an abundance of data regarding transfer payments in Kamloops. This census notably included data from both 2019 and 2020 to provide information relating to the pandemic. In the wake of the pandemic, 12,105 more Kamloops residents received government transfer payments than in the year prior. Over the same time frame, the median transfer amount per recipient increased by $2,450, from $7,750 in 2019 to $10,200 in 2020. Similarly, the number of people on employment insurance increased by 24%, with the median employment benefits increasing marginally from $5,400 to $5,520 per recipient. As expected, the biggest change during this time was due to COVID-19 recovery benefits. Out of Kamloops’ 66,390+ working-age population, 19,155 received some form of COVID-19 pandemic relief. Additional noteworthy figures regarding transfer payments from the 2021 Kamloops census are detailed below in Table 1.

Table 1: Government Transfer Payments, Kamloops, BC

| Skip Table 1 | |||

| Transfer payments | 2019 | 2020 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of government transfers recipients aged 15 years and over in private households – 100% data | 51,945 | 64,050 | 12,105 |

| Median government transfers among recipients ($) | 7,750 | 10,200 | 2,450 |

| Number of employment insurance benefits recipients aged 15 years and over in private households -100% data | 6,300 | 7,810 | 1,510 |

| Median employment insurance benefits among recipients ($) | 5,400 | 5,520 | 120 |

| Number of COVID-19 emergency and recovery benefits recipients aged 15 years and over in private households in 2020 – 100% data | 0 | 19,155 | 19,155 |

| Median COVID-19 emergency and recovery benefits in 2020 among recipients ($) | 0 | 8,000 | 8,000 |

Note. Data from Statistics Canada (2023).

In this time frame, COVID-19 government income support and benefits comprised almost 10% of the total income of the population aged 15+. In terms of composition of total income, from 2019 to 2020, government transfers as a proportion of private household income increased by 5%, the same magnitude with which employment income decreased. It is important to note that COVID-19 government income support and benefits, as well as emergency and recovery benefits, made up almost 10% of the total income of the population aged 15+. Table 2 includes more income information related to this population group. This may be interpreted as a successful allocation of public funds since it provided a social safety net to the people. Therefore, some may interpret the federal fiscal response to COVID-19 as a success since the transfer payments seem to broadly “make up” for lost employment income. However, the question of the appropriate allocation of public funds requires a more granular and qualitative lens than a sliver of census data generally allows for.

Table 2: Kamloops Income & Transfers

| Skip Table 2 | |||

| Composition of Total Income of the Population Aged 15 Years and Over in Private Households (%) — 25% Sample Data | 2019 | 2020 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market income (%) | 87.8 | 82.6 | -5.2 |

| Employment income (%) | 71.8 | 66.8 | -5.0 |

| Government transfers (%) | 12.3 | 17.5 | 5.2 |

| Employment insurance benefits (%) | 1.2 | 1.3 | 0.1 |

| COVID-19 – Government income support and benefits (%) | 0.0 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

| COVID-19 – Emergency and recovery benefits (%) | 0.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

Note. Data from Statistics Canada (2023)

We can expect this swath of transfer payments to affect the income distribution in Kamloops. This chapter aims to quantify any such impact for the knowledge of all taxpayers.

Literature Review

Classical economists primarily concerned themselves with the apportionment of income based on various factors of production (land, labour, and capital), as opposed to the distribution of household income. Nonetheless, there is a growing body of literature on income inequality and its multitudinous implications. The relationship between income inequality and poverty, economic growth, health, happiness, social cohesion, and many other variables has been examined at length (Kuznets, 1985; Shin, 2012; Subramanian & Kawachi, 2004; Oishi, 2011; Wilkinson, 1999).

In recent years, economists have added the pandemic as another key variable to be examined alongside inequality. Numerous studies use inequality as the predictor variable, measuring health and social outcomes in response. A smaller body of research exists on the effect of the pandemic and pandemic policies (Clark et al., 2021; Deaton, 2021; Elgar et al., 2020; Bonacini et al., 2021; Su et al., 2022). This study draws on some of the existing COVID-19 inequality research, but with a focus on the effect of pandemic transfer payments on income inequality.

The subject has been studied in regions of varying sizes across different lengths of time. There is a growing literature focused on income inequality in Canada and its massive regional variances (House of Canada, 2013; Marchand et al., 2020; McLeod et al., 2003). The province of British Columbia has received some research attention, particularly regarding the disparities between the wealth concentrated in Metro Vancouver as compared to rural, interior, and coastal communities (Cunningham et al., 2011; Wallis, 2006; Veenstra, 2002). However, there is virtually no existing research focused on economic inequality in the interior, especially not in the Thompson-Nicola Regional District. This study attempts to address that gap, as there is merit in examining income distribution at the municipal level, even for smaller communities.

Among numerous methods used to measure income inequality, by far most popular and widely cited is the Lorenz curve. Introduced by the economist Max Lorenz in his 1905 paper “Methods of Measuring the Concentration of Wealth,” this tool allows researchers to compare and graphically display income inequality across time and place. Each cumulative percentage of the population is plotted against its share of the total income earned. Albeit simple, the Lorenz curve is both useful and well-known in the study of wealth distribution.

Dividing the area between the line of perfect equality and the Lorenz curve by the total area gives a value known as the Gini coefficient (Gini, 1912). The value of the Gini coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality) to 1 (perfect inequality). For context, according to the latest figures from Our World in Data, the global Gini values range from approximately 0.28 (in Finland, Norway, and Poland) to approximately 0.55 (Brazil, Columbia, and Zimbabwe) (World Bank Poverty and Inequality Platform & Our World in Data, 2024). Finally, it is important to note that the Gini coefficient, just like the Lorenz curve, is a narrow tool that gives a small but important piece of the picture.

Methodology

Income data was pulled from the 2021 Kamloops Census to generate original Lorenz curves (Statistics Canada, 2023). Due to the pandemic, the 2021 census included responses from both 2019 and 2020. To isolate the effects of transfer payments, two different income datasets were analyzed: employment income (EI) and labour-market-related income (LMRI). The former is self-explanatory — income gained through wages, salaries, and tips. The latter includes employment income but is also comprised of other benefits, such as employment insurance and pandemic relief. Transfer payments are only included in the LMRI, so analyzing the employment income allows partial control for the numerous labour market changes caused by the pandemic. From these two datasets and two years’ worth of data, it is possible to generate four unique Lorenz curves and Gini indices. Since no regression is possible with this limited data set, significance and conclusions will be drawn from any disparities in the Gini coefficients.

Results

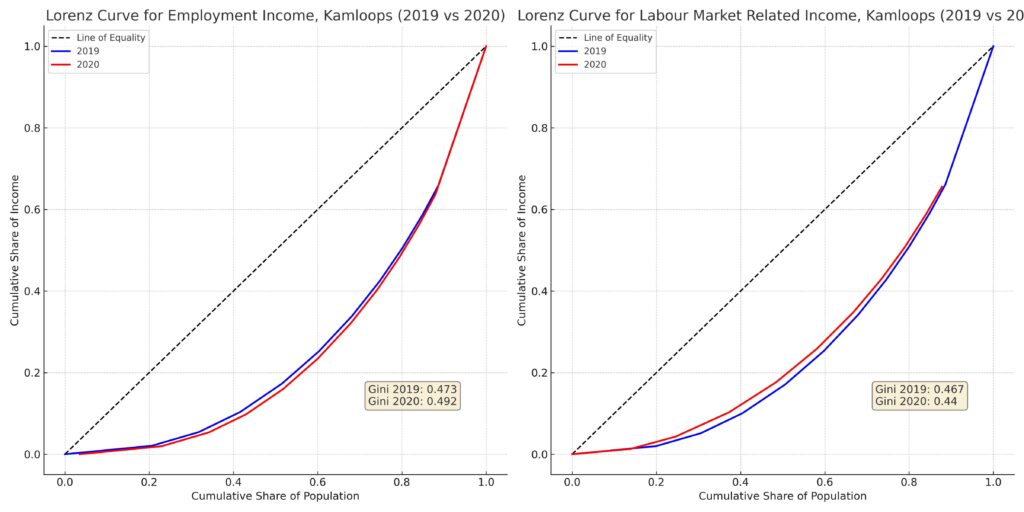

Figure 1 shows the employment income analysis (without transfer payments) from 2019 to 2020. The second figure shows the change in the labour market relative income from 2019 to 2020. For employment income, the Gini coefficient increased significantly from 0.473 to 0.492, an amount of 4%. This change is from year to year and does not take into account the dynamic changes that happened in the early stages of COVID-19 and the shutdown of the Canadian economy. The increase is mainly due to 2010 employed people in the employment pool in 2020 relative to 2019. When examining the labour-market-related income, we see the Gini index moving towards more equality in 2020 relative to 2019. The Gini index decreased from 0.467 to 0.440, or a 4.8% decrease in the Gini Index.

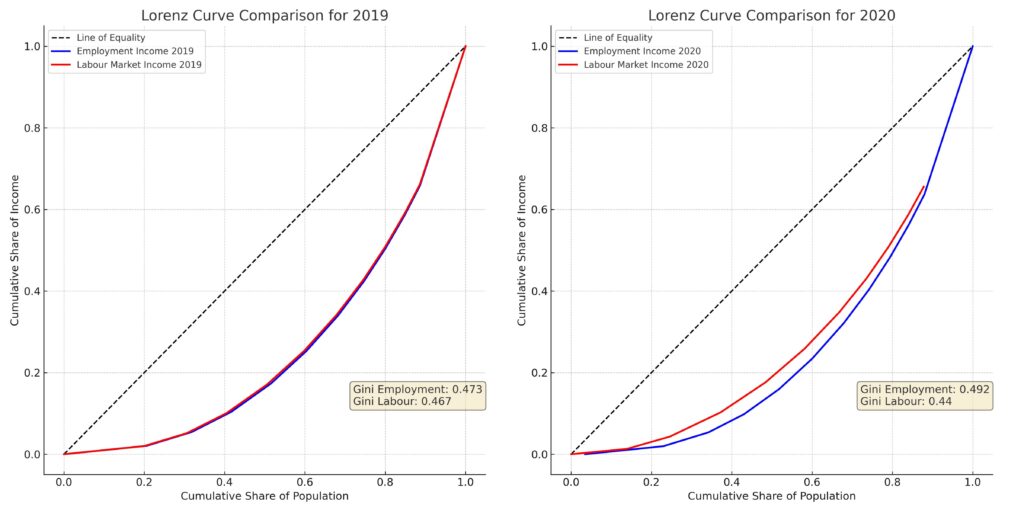

Figure 2 shows the results of comparing employment income and labour-market-related income (with transfer payments) for 2019 and 2020, respectively. For 2019, the year with no pandemic, there was a decrease in the Gini coefficient from 0.473 with employment income to 0.467 with transfers or a 1.3% decrease, which shows that transfers in normal periods bring more equality to the community. Examining the difference between employment income (without transfers) and labour-market-related income for 2020 shows a large decrease in inequality. The Gini index measured with employment income is 0.492 while the labour-market related income (with transfers) reduces to 0.440 or ~11% decrease.

Table 3 provides a summary of the Gini index and how it changes over time and across income types. As stated above, the Gini index for employment income changed by a minuscule amount from 2019 to 2020. But for employment income after including transfer payments, the Gini index fell by 6.4%, indicating

a reduction in inequality. Also, examining the role of transfer payments in 2019 and 2020 shows that in 2019, transfer payments reduced the Gini index by 1.3%, but in 2020, transfer payments reduced the Gini index by 7.6%.

Table 3: Gini Index and Transfer Payments Pre- and During COVID-19 Years

| Skip Table 3 | |||

| Variable of Interest | 2019 | 2020 | Change in Gini Index |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Income | 0.473 | 0.492 | -4% |

| Labour-Market-Related Income | 0.467 | 0.440 | -5.8% |

| Change in Gini Index | -1.3% | -11% | — |

Discussion

From 2019 to 2020, employment income inequality in Kamloops increased by 4%. Keynes’ theory of sticky wages — that employees’ compensation remains fixed or “sticky” in times of economic hardship rather than falling — suggests that layoffs will occur as a result (Keynes, 1936). According to the Labour Force Survey conducted by Statistics Canada, nearly two million Canadians were furloughed or laid off in April 2020 alone (Statistics Canada, 2020). Of course, this amounts to approximately two million fewer employment income earners. If the displaced two million employment income earners were distributed evenly across the income distribution, the Gini index (and hence, inequality) would not have changed. However, the pandemic primarily disrupted lower-income wage jobs (in hospitality, retail, food and beverage, etc.) as opposed to salaried positions (Blum, 2021; Gould & Kassa, 2021), one might predict an increase in income inequality.

Employment Income

For the sake of this research, there were 2,010 fewer people in the employment pool; when the income distribution is adjusted for the loss of employment income of the 2,010 workers, inequality as measured by the Gini index increases by 4% from 0.473 in 2019 to 0.492 in 2020. It could be possible that the distribution within an income range may have changed from 2019 to 2020, making inequality even more severe as measured without transfer payments. Table 4 shows fewer people at the bottom decile of the income distribution relative to the top half of the income distribution from 2019 to 2020, supporting the proposition that the lower-income wage jobs were affected more severely. Not accounting for the 2,010 people who withdrew, 2,200 fewer people are working from the bottom half of the distribution, and 190 more people in the upper half of the income distribution. There was a notably increase in those who earn over $100,000: 380 more people during COVID-19 relative to 2019.

Labour-Market-Related Income

Looking at labour market income, we observe almost the same participants in 2019 and 2020. There are 3,480 fewer people earning under $10,000 in 2020 relative to 2019 and more people earning in the higher income groups. We also observe a 5.8% decrease in inequality, which is expected due to significant government spending on transfer payments to mostly the unemployed with low-income wage jobs. The impact of transfer payments can also be seen in 2020, where transfer payments decreased the Gini index by 11% relative to 2019, which decreased the Gini index by 1.3%. Table 21 shows the change in the number of people in the different income groups.

Table 4: Distribution of Income in Kamloops, 2019 & 2020

| Skip Table 4A | ||||

| Income Group | Mid Point Income | 2019 | 2020 | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $10,000 | 5,000 | 11,930 | 11,255 | -675 |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 15,000 | 6,435 | 6,510 | 75 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 25,000 | 5,715 | 5,125 | -590 |

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 35,000 | 5,725 | 5,040 | -685 |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 45,000 | 5,090 | 4,765 | -325 |

| $50,000 to $59,999 | 55,000 | 4,540 | 4,545 | 5 |

| $60,000 to $69,999 | 65,000 | 3,790 | 3,620 | -170 |

| $70,000 to $79,999 | 75,000 | 3,095 | 3,040 | -55 |

| $80,000 to $89,999 | 85,000 | 2,775 | 2,740 | -35 |

| $90,000 to $99,999 | 95,000 | 2,155 | 2,220 | 65 |

| $100,000 and over | 150,000 | 6,575 | 6,955 | 380 |

| Total | — | 57,825 | 55,815 | -2,010 |

| Skip Table 4B | ||||

| Income Group | Mid Point Income | 2019 | 2020 | difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Under $10,000 | 5,000 | 11555 | 8075 | -3480 |

| $10,000 to $19,999 | 15,000 | 6205 | 6205 | 0 |

| $20,000 to $29,999 | 25,000 | 5745 | 7320 | 1575 |

| $30,000 to $39,999 | 35,000 | 5855 | 6475 | 620 |

| $40,000 to $49,999 | 45,000 | 5390 | 5665 | 275 |

| $50,000 to $59,999 | 55,000 | 4710 | 5010 | 300 |

| $60,000 to $69,999 | 65,000 | 3870 | 3930 | 60 |

| $70,000 to $79,999 | 75,000 | 3185 | 3190 | 5 |

| $80,000 to $89,999 | 85,000 | 2820 | 2840 | 20 |

| $90,000 to $99,999 | 95,000 | 2165 | 2245 | 80 |

| $100,000 and over | 150,000 | 6610 | 7085 | 475 |

| Total | — | 58110 | 58040 | -70 |

Note. Data from Statistics Canada (2023)

Conclusions, Limitations, & Future Research

While employment income inequality increased by 4% from 2019 to 2020, reflecting the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on lower-wage earners, the inclusion of government transfer payments reversed this trend. Labour-market-related income, which includes transfers, saw a 5.8% reduction in inequality, and the Gini index for 2020 fell by 11% when factoring in the pandemic-related benefits. These results indicate that the government’s fiscal response, including programs like CERB and CEWS, somewhat successfully reduced income disparities in Kamloops and provided financial relief to those most affected by job losses. The reduction in the Gini coefficient with transfer payments shows the effectiveness of these measures in counteracting the pandemic’s economic fallout.

Any economist worth her salt acknowledges trade-offs where they exist. While Lorenz curve analysis is relatively straightforward to conduct and intuitive to analyze, it is limited in scope. The findings of this study give little information about well-being, population growth, or other complex factors. In order to be concise and impactful, it focuses on the sole dimension of income inequality. Furthermore, in the absence of more detailed individual income data, cumulative earnings and population values had to be estimated rather than exact. The author acknowledges this may have resulted in some inaccuracies, especially on the upper end of the distribution. For example, Statistics Canada (2023) simply denotes the highest income bracket as $150,000+, meaning it is difficult to identify how extremely high-income individuals would affect the distribution. Finally, it is important to recognize that the Lorenz curves and Gini coefficients found serve as just one measure of a complex issue. As improperly allocated COVID-19 benefits continue to be recalled, the true state of income inequality in Kamloops ought to be investigated.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Tsigaris for his endless patience, insight, and wit throughout this project. I’m also deeply grateful to the entire 2024 ECON 4980 team for their feedback and support. Thanks for a great year!

Media Attributions

Figure 1: “Lorenz curves for employment and labour-market-related income (2019 vs. 2020) graphs” [using data from Statistics Canada (2023)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 2: “Lorenz curve employment and labour-market-related income comparisons for 2019 and 2020 graphs” [using data from Statistics Canada (2023)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 3: “Olivia Simms’ poster presentation at the 19th TRU Undergraduate Research Conference in March of 2024” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Blum, B. (2021, February 23). Low-wage earners hit hardest by pandemic job market . CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/job-losses-pandemic-lower-income-1.5922401

Bonacini, L., Gallo, G., & Scicchitano, S. (2020). Working from home and income inequality: Risks of a ‘new normal’ with covid-19. Journal of Population Economics, 34, 303–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-020-00800-7

Cunningham, C. M., Hanley, G. E., & Morgan, S. G. (2011). Income inequities in end-of-life health care spending in British Columbia, Canada: A cross-sectional analysis, 2004-2006. International Journal for Equity in Health, 10, Article No. 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-10-12

Deaton, A. (2021). Covid-19 and global income inequality (Working Paper 28392). National Bureau of Economic Research Working Papers. https://doi.org/10.3386/w28392

Gatehouse, J. (2020, December 6). Ottawa has spent $240B fighting covid-19 in just 8 months. A CBC investigation follows the money. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/tracking-unprecedented-federal-coronavirus-spending-1.5827045

Gini, C. (1912). Variabilità e mutabilità: Contributo allo studio delle distribuzioni e delle relazioni statistiche [Variability and mutability: Contribution to the study of distributions and statistical relations]. Tipografia di Paolo Cuppini.

Gould, E., & Kassa, M. (2021, May 20). Low-wage, low-hours workers were hit hardest in the COVID-19 recession: The State of Working America 2020 Employment Report. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/swa-2020-employment-report/

House of Commons Standing Committee on Finance. (2014). Income inequality in Canada: An overview (Report No. 3). Parliament of Canada. https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/41-2/FINA/report-3/

Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest, and money. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kuznets, S. (1985). Economic growth and income inequality. In The Gap between rich and poor: Contending perspectives on the political economy of development (1st ed.). Routledge.

Lorenz, M. O. (1905). Methods of measuring the concentration of wealth. Publications of the American Statistical Association, 9(70), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/15225437.1905.10503443

Marchand, Y., Dubé, J., & Breau, S. (2020). Exploring the causes and consequences of regional income inequality in Canada. Economic Geography, 96(2), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1715793

MacLeod, A. (2015). A better place on earth: The search for fairness in super unequal British Columbia. Harbour Publishing.

McLeod, C. B., Lavis, J. N., Mustard, C. A., & Stoddart, G. L. (2003). Income inequality, household income, and health status in Canada: A prospective cohort study. American Journal of Public Health, 93(8), 1287–1293. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.8.1287

Oishi, S., Kesebir, S., & Diener, E. (2011). Income inequality and happiness. Psychological Science, 22(9), 1095–1100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417262

Panizza, U. (1999). Income inequality and economic growth: Evidence from the American data. Journal of Economic Growth, 7(1), 25–41. https://doi.org/10.18235/0011000

Shin, I. (2012). Income inequality and economic growth. Economic Modelling, 29(5), 2049–2057. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2012.02.011

Statistics Canada. (2023). Census profile, 2021 census of population (No. 98-316-X2021001) [Table]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Su, D., Alshehri, K., & Pagán, J. A. (2022). Income inequality and the disease burden of Covid-19: Survival analysis of data from 74 countries. Preventive Medicine Reports, 27, Article No. 101828. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.101828

Subramanian, S. V., & Kawachi, I. (2004). Income inequality and health: What have we learned so far? Epidemiologic Reviews, 26(1), 78–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxh003

Veenstra, G. (2002). Income inequality and health. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 93, 374–379. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03404573

Wallis, K. D. (2006). Inequality in British Columbia: What role does tax policy play? [Master’s thesis, University of British Columbia]. UBC Theses and Dissertations. https://dx.doi.org/10.14288/1.0077623

Wilkinson R. G. (1999). Income inequality, social cohesion, and health: Clarifying the theory—A reply to Muntaner and Lynch. International Journal of Social Determinants of Health and Health Services, 29(3), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.2190/3QXP-4N6T-N0QG-ECXP

World Bank Poverty and Inequality Platform [with major processing by Our World in Data]. (2024). Gini coefficient – World Bank [Data set]. Our World in Data. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/economic-inequality-gini-index

Long Descriptions

Both graphs:

- X-axis — Cumulative Share of Population

- Y-axis — Cumulative Share of Income

- Line of Equality

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (1, 1)

Employment Income graph:

- 2019 (blue)

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (0.88, 0.65)

- 2020 (red)

- Start — (0.02, 0)

- End — (1, 1)

- The 2019 curve is slightly higher than the 2020 one.

Labour-market-related income graph:

- 2019 (blue)

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (0.88, 0.65)

- 2020 (red)

- Start — (0.15, 0.01)

- End — (1, 1)

- The 2020 curve is slightly higher than the 2020 one.

Both graphs:

- X-axis — Cumulative Share of Population

- Y-axis — Cumulative Share of Income

- Line of Equality

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (1, 1)

2019 graph

- Employment income (blue)

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (0.88, 0.65)

- Labour-market-income (red)

- Start — (0, 0)

- End — (0.88, 0.65)

- The curves line perfectly overlap

2020 graph

- Employment income (blue)

- Start — (0.02, 0)

- End — (1, 1)

- Labour-market-related income (red)

- Start — (0.15, 0.01)

- End — (1, 1)

- The labour-market-related income curve starts off overlapping with the employment income curve, but its curve becomes steeper than the other one around (0.15, 0.01).