7 Cultural Alchemy: Navigating the Economic Challenges in the Performing Arts Centre

Samreena Noor

Introduction

This research study explores the socioeconomic and political factors around having a performing arts centre in Kamloops. Furthermore, the study will examine the potential of a subsidy through increased municipal taxes that allows for free entrance for citizens who do not have the means to pay, making the centre an inclusive place to enjoy. Performing arts centres contribute to their local communities’ cultural and artistic development, ultimately enhancing civilians’ quality of life (Kim & Seung-Hye, 2015). Performing arts centres are important in promoting cultural welfare, enhancing cultural vibrance, and improving morale. The outcome of whether to build the performing arts centre depends on philanthropy, tax, and policy recommendations made by the municipal government.

On February 6, 2024, the council approved the 7-million-dollar architectural plan for a performing arts centre (Peters, 2024). The project will be built on city-based land on Seymour Street at Fourth Avenue in downtown Kamloops. The detailed design is expected to be completed around the end of 2025, with a two-year construction timeline plan for completion. The positive externalities of performing arts centres in cities are well-researched in academic literature, as showcased throughout the research paper. Positive externalities are benefits that accrue for the community members at large who do not participate in market transactions associated with the performing arts centre. Markets or public authorities will underprovide, or not even provide, such goods if they do not consider the external benefits of performing arts centres to their community.

As former Kamloops Mayor Ken Christian stated when asked what role the city sees the performing arts centre playing in enhancing the overall quality of life for the residents of Kamloops, he replied that there is an “underinvest[ment] into the culture of performing arts centre. We embarked on the path to fix that.”

The performing arts centre positively impacts the economic and cultural development of cities, and as research illustrates, it increases the attractiveness of cities to residents and non-residents (Pashkus et al., 2021; Ong & Deanna, 2022; Ardyanto & Rachman, 2022). Ken Christian was asked how the city of Kamloops envisions the performing arts centre contributing to economic development: he said that the performing arts centre in Kamloops not only serves as a regional facility but also significantly impacts the economy. According to the former mayor and his team, each tourist contributes approximately $140 to the local economy.

“There needs to be a recognition of people who love the arts. There are people who are employed in running the place, there are people who are living in the venue and there are employment opportunities. It gives people the opportunity to see themselves developing themselves in that profession. It is the same principle for seeing people for sports compared to performing arts.”

— Ken Christian, Former Kamloops Mayor (K. Christian, personal communication, March 26, 2024)

Methodology

This research study draws on primary and secondary sources to assess the impact of philanthropy and the role of positive externalities with the performance arts in Kamloops City. The primary sources are key interviews with the key stakeholders in Kamloops. This study also examines secondary data to assess the positive externalities of the performing arts centre and the role of philanthropists in supporting the provision of this centre. The qualitative research involves interviews with key stakeholders in semi-structured open-ended questions, including:

- How does the performing arts centre improve Kamloops’ quality of life?

- Why approve the performing arts centre now after past rejections from referendums?

- How will the centre aid Kamloops’ economic growth?

- Will the centre attract professionals, such as doctors?

- What are the costs and funding plans for the centre?

- How will the city make the centre accessible and inclusive?

- Will the centre be affordable for low-income individuals?

Additionally, information was analyzed from secondary sources, such as academic journals and industry publications. This study explores the literature about the role of philanthropy in supporting the performing arts centre, including donations, grants, sponsorships, and their time. Secondary sources examining the positive externalities include studies exploring community engagement, cultural benefits, and social capital. This methodology attempts to show the significance of positive externalities and philanthropy in building the performing arts centre in Kamloops. In summary, the purpose of this chapter is to accentuate how important a performance arts centre is by examining the positive externalities and philanthropy in supporting such a project.

Background Information

The discussion about building a performing arts centre in Kamloops appears to have started around 2004 and 2005. In 2015, a referendum was held on a proposal to borrow up to $49 million to build a performing arts centre and an underground parkade (CBC News, 2015). The referendum failed, with 53.7% of the voters voting against the proposal. The city had already purchased the former Kamloops Daily News building for $4.8 million to use as the site for the centre.

It is worth considering that using referendums for projects such as a performing arts centre, which offers positive externalities and long-term economic and cultural benefits, may not always be effective. This is because the economic outcome and rationale for building such a centre may conflict with private interests that seek to use the centre. Public choices are made by evaluating the private benefits that one would receive from the project and the taxes that must be paid to finance the project. If the private benefits are less than the taxes the project requires, the company will vote against it, even if it benefits the community more than it costs. Therefore, the private interests dictate the outcome rather than the collective interest.

Hypothetical Referendum Example

The following hypothetical example in Table 1 illustrates the issue. Suppose that 73,000 eligible voters have a distribution of valuation of the centre, as indicated in the first two columns. For example, 50,000 households are willing to pay a maximum of $5 a year each for the city to have the centre, another thousand are willing to pay $300 each, and so on. This is how much each person values the performance centre. The total valuation of the project would then yield ~$1.5 million of benefits each year, not including the external benefits, and it exceeds the costs estimated at $900,000 a year. If the city increases taxes, say property, per household of two people, to $40 a year, the cost would be covered. But when the day to vote arrives, those whose maximum amount they are willing to pay is less than the tax will vote no, and those whose benefits exceed the taxes will vote yes. Counting the ballots shows that out of a total of 23,000 people who voted, 12,000 (52.8%) voted no and 11,000 (47.2%) voted yes. Accidentally, the outcome of this hypothetical example is very close to the actual outcome of the 2015 referendum. This hypothetical example shows that projects that are worth undertaking, even not accounting for the external benefits, should not be put to a referendum but have the demographically elected council and mayor decide whether to go ahead or not, as they represent the city’s people.

Table 1: Hypothetical Referendum Outcome

| Skip Table 1 | |||||||

| People | Max WTP | Taxes per household per year | Total Max WTP | Total taxes | Referendum | No Vote | Yes Vote |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50,000 | 5 | 40 | 250,000 | 500,000 | Did not vote | 0 | 0 |

| 1,000 | 10 | 40 | 10,000 | 20,000 | No | 1,000 | 0 |

| 2,000 | 20 | 40 | 40,000 | 40,000 | No | 2,000 | 0 |

| 4,000 | 30 | 40 | 120,000 | 80,000 | No | 4,000 | 0 |

| 5,000 | 35 | 40 | 175,000 | 100,000 | No | 5,000 | 0 |

| 5,000 | 40 | 40 | 200,000 | 100,000 | Yes | 0 | 5,000 |

| 3,000 | 80 | 40 | 240,000 | 60,000 | Yes | 0 | 3,000 |

| 2,000 | 100 | 40 | 200,000 | 40,000 | Yes | 0 | 2,000 |

| 1,000 | 200 | 40 | 200,000 | 20,000 | Yes | 0 | 1,000 |

| 73,000 | — | — | 1,435,000 | 960,000 | — | 12,000 (52.2%) | 11,000 (47.8%) |

Note. Total taxes are computed assuming two people per households and that half of the households that did not vote will pay taxes.

See Kamloops This Week’s (2015) article comparing the operating costs of the performing arts centre with other city buildings for more background information.

2020 Referendum

In 2020, there were plans for another referendum on a $70 million performing arts centre to be built at the site of the former Kamloops Daily News building. However, this referendum was cancelled due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Petruk, 2023). Pre-pandemic time, on April 4, 2020, the Kamloops residents were preparing to vote in a second referendum held on a performing arts centre (Petruk, 2023). However, the vote on the centre planned for a property on Seymour Street, Fourth Avenue, and St. Paul Street was postponed due to the pandemic (Petruk, 2023). A ‘yes’ vote would have allowed the City of Kamloops to borrow up to $45 million for the $70 million project, almost double the amount planned during the 2015 referendum at $45 million (CFJC, 2022). This second referendum failed because the pandemic created socioeconomic turmoil, and the performing arts centre was not a priority. It is not a fair analysis to put this project up for a referendum because the public voters base their vote on their private benefits and private costs that accrue for their individual needs and not the community at large, as illustrated previously. The referendums are biased toward the voters’ tastes and preferences and do not look at the economic benefit in the long term.

What motivated the city to approve the performing arts centre this time, given that the plan has been rejected before in referendums?

“The pandemic caused a huge impact. The arts were cancelled, everything stopped, the uncertainty from the pandemic — the job loss, the government Municipal of Affairs cancelled the performing arts centre. The performing arts is in the works for 20 years and there was one referendum that had been failed. A change in the design, the security in the location, and a better financing — a benefactor have brought it now to the forefront. Regarding parking, high-income families are the ones with cars. Look at the hockey, there will be parking spaces and parking from away. The latest plan for the performing arts will satisfy the parking concern — parking for people who work there. There needs to be a look after all the people.”

— Ken Christian, Former Kamloops Mayor (K. Christian, personal communication, March 26, 2024)

The performing arts project is again at the forefront of the planning process now that the pandemic is over. There were rumours that a referendum on the performing arts centre could be held again in the fall of 2023, but the mayor stated he had “no idea” if this would happen.

In 2024, the City of Kamloops council agreed to allocate $7 million to complete the design phase for the long-proposed performing arts centre, which would cost $120 million (Holliday, 2024a). The council approved the initial plan on February 6, 2024, and discussed the funding recommendations. Counsellor O’Reilly states “we believe this is the right project, in the right place, at the right time.” This showcases how Kamloops is ready for a performing arts centre after slowly recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic. The recommendation was approved by an 8–1 vote, and the project is now underway. Current estimated cost is $154 million of which up to $140 million will come from local taxpayers (Rothenburger, 2024b).

An Alternative Approval Process?

Currently there is an alternative approval process (i.e., a counter petition) for the PAC. To oppose the approval, 10% of the electorate would have to petition against the process. The AAP was selected by city council as a preferred method of community engagement relative to another referendum and was used in the past to vote for the state-of-the-art water filtration system. The AAP assumes that the electorate has opted-in, except if they decide to opt-out by filling out a form opposing the approval. This opt-out system is similar to organ donations. An opt-out system assumes everyone initially is a donor (i.e., everyone wants the PAC) unless they specifically decline, and it results in higher donor rates (i.e., higher acceptance rates) relative to an opt-in system which requires people to actively register as donors (i.e., actively vote in favour of the PAC). The opt-in often leads to lower donor rates (Shepherd et al., 2014). Opting-in leads to a lower acceptance rate of the PAC.

The voting started on Aug 6, 2024, and ends on September 13, 2024, with forms available from City Hall, can be found online or requested by email. The form states:

I am OPPOSED to the City of Kamloops proceeding with adopting Kamloops Centre for the Arts Loan Authorization Bylaw No. 57-1, 2024, authorizing borrowing $140,000,000 to be repaid over a period not exceeding thirty (30) years, to finance the Kamloops Centre for the Arts, described on Page 2 of this form, unless a referendum vote is held.

(Rothenburger, 2024a)

To oppose the City of Kamloops to proceed with the borrowing, it would require 8,713 votes out of 87,131 eligible voters. Rothenburger (2024a) is in favour of the PAC but believes that for such mega projects a referendum is appropriate relative to the AAP because it leaves no doubt as to what people want relative to AAP which assumes initially that all 87,131 eligible voters want the project except if at least 8,713 vote against the project during the AAP. In 2003 a referendum instead of an AAP was held for the Tournament Capital Centre with 54% of voters in favour of the project (Holliday, August 22). The results of the AAP, announced on September 23, 2024, revealed that the plans for a performing arts centre and iceplex would proceed after the opposition fell short of the 10% threshold (Rothenburger, 2024b).

Although referendums are an effective way to vote for public projects there is a problem in that people vote based on the maximum amount, they are willing to pay (i.e., their private valuation) relative to the taxes they are expected to pay for the project (i.e., their costs) and do not take into account the external benefits of the project. As the hypothetical example showed by Table 17 even if the private benefits exceed the costs of the project, a referendum may result in the project being defeated. Hence, a referendum also may not be an ideal process for voting on mega projects as each individual voter looks at their own private benefit and cost ignoring the collective benefits of a major project. How can then mega projects be undertaken if a referendum does not materialize in the collective good of a community? There is not a right answer or solution to this dilemma. However, perhaps members of the Kamloops Council during their campaign elections with their platform can illuminate the potential external benefits of such projects?

“‘MIXED EMOTIONS’ might be a good way to describe the outcome of the alternative approval process on borrowing for a new performing arts centre and an arena. I’ve been clear about my support for building a PAC. I wasn’t invested in the iceplex project but I’ve backed the PAC since 2003 when it was put into our cultural strategic plan. As mayor at the time, I tried very hard to get it built long ago but didn’t get it done. At long last, it will become a reality……..The PAC will do much to repair the imbalance between sports and the arts in Kamloops. It’s going to be beautiful. It’s going to be a place that brings together all Kamloops residents, not just the “elite” as some claim.”

— Mel Rothenburger, The Armchair Mayor (2024c)

Public Concerns About the Performing Arts Centre

In 2015, members of the public were concerned with the costs of building the performing arts centre and how the funds could be used on other projects (Reynolds, 2015). Since the centre is a largely publicly funded project, the majority of the votes showcased ‘no’ as the public wanted a more improved project. The referendum was unclear and left numerous unanswered questions for the taxpayers to help support this project. Therefore, the city staff believed that the result of the performing arts centre project would allow the city to focus on more important projects. It is important to note that during this time, a portion of the performing arts centre’s funding would come through the Gas Tax and Gaming Fund Reserve. This money is collected from the sales of fuel, lottery tickets, and the city’s savings account (Reynolds, 2015). The PAC Not Yet campaign argues that these funds should be focused on infrastructure, such as fixing the roads, upgrading the water systems, and improving accessibility throughout the city.

This research acknowledges the public’s concerns about the funding for the performing arts centre, as the referendum may not have enough information about the full purpose and importance of having an arts centre. This research will delve deeper into the positive benefits of having a performing arts centre as well as utilizing the possibility of philanthropy to alleviate the cost concerns.

How to Make the Performing Arts Centre More Inclusive

Making the performing arts centre more inclusive would reduce public concerns and increase the demand for such a project. The increased demand would increase the value people place on the centre and make the voters who voted no in the past referendum change their minds and support it, provided the higher private benefits exceed the taxes to partially finance the operation of the centre. Also, finding philanthropists to finance the project would reduce the taxes that people would need to pay. One of the main reasons people voted in favour of the Tournament Capital Centre in the referendum was that they saw it as being inclusive. Suggestions and calls to action to make the performing arts centre more inclusive include:

- Diverse and a wide range of performances celebrating different cultures — This will touch various cultural, socioeconomic, and age groups. It may include different genres of music, theatre, dance art, and more. These performances celebrate different cultures and traditions and can make the members of the community feel represented. For example, months that celebrate history and holidays (such as Black History Month and Holi), Indigenous storytelling sessions, and much more can enhance community vibrancy and the use of the performing arts centre. The performing arts centre’s committee can partner with local cultural organizations (e.g. the Kamloops Multicultural Society, Kamloops Hindu Cultural Society, Sikh Cultural Society, and Kamloops Aboriginal Friendship Society) to co-produce events and ensure the authenticity of the events and wide local support.

- Affordable pricing system — The performing arts centre can implement a pricing system including discounts for children under 12, students, and seniors to ensure that the financial constraints do not prevent members of the community from attending shows. The centre can introduce a tiered ticket system for seats and additional perks; for example, the seats closer to the stage cost more compared to the seats at the back.

- Outreach programs for local schools — Elementary and secondary students could use the performing arts centre for their performances, plays, and music practice space. There could be after-school programs with local schools to use the space, which will help nurture young talent and interest in the arts.

- Partnerships with local artists and groups — The performing arts centre can collaborate with local artists to create performances that showcase their work on a larger platform. For example, there can be a local artist program that supports local artists and helps integrate their work into the community, which strengthens community engagement. The centre can dedicate certain dates to showcase local artists’ projects and include community-based work in the performances.

- Accessibility measures — The facility needs to be physically accessible to individuals with disabilities. This includes wheelchair access, sign language interpretation, and sensory-friendly performances for individuals with sensory processing disorders. An action that could be implemented by the centre is providing performances where the lighting and sounds are adjusted for sensory-sensitive individuals.

Positive Externalities From the Performing Arts Centre

It is important to note that consumers have different tastes and cultural preferences but do not consider the benefits the community receives when they make choices. The performing arts centre is known in economics as a private good with characteristics of rivalry and excludability. Rivalry demonstrates how the consumption of the good by one person reduces the amount available for others. For instance, if someone occupies a seat in a show at the centre, nobody else can occupy that same seat. If a good is excludable, it prevents people who have not paid for it from accessing it. The centre can prevent people who have not bought a ticket from entering the centre. However, a performing arts centre yields numerous positive externalities which may not be captured in the ticket price of performing arts shows and exclude many low-income people from attending. For example, if a person purchases a ticket, then the good is available to them. However, if an individual does not purchase a ticket, then they cannot watch a show at the performing arts centre.

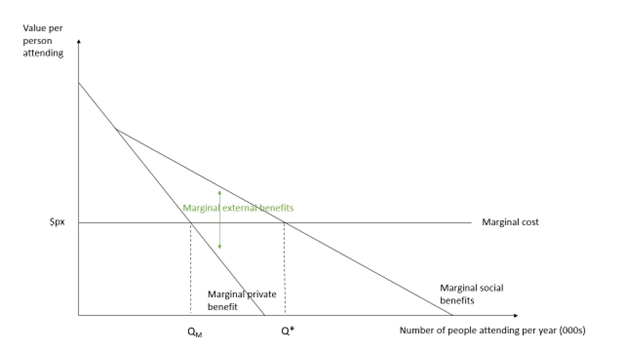

A positive externality, also known as external benefits, is the economic activities that positively impact a third party. In the environment of cultural economics, there would be positive externalities from the performing arts, which would require some form of subsidy to internalize these external benefits. There needs to be a subsidy because markets or municipal authorities will produce a level of output that balances and equates the marginal benefits to the consumer of the good and the marginal costs to suppliers but may not consider the external benefits the good provides to the community. With the presence of positive externalities, the marginal social benefit of the performing art centre will exceed the private marginal cost, and hence, all benefits that accrue for the community are not captured, leading to a level of output that is too little relative to the socially optimal level. Providing a subsidy will increase the usage of the centre by more people, especially low-income families that cannot afford to go to the centre. Hence, a solution to capture the external benefits would be to provide a subsidy to increase attendance and make it inclusive for all communities.

The graph below illustrates an economic representation of the social and private benefits and costs associated with attending the performance art centre. The marginal private benefits are the benefits that those who attend the centre receive. Each point on the curve represents the maximum amount the consumers are willing to pay (MaxWTP) to attend and enjoy shows over a given period of time. The marginal external benefit (MEB) is the benefit that people other than the consumers receive from having the centre. These are the positive externalities of having the centre operate and includes things like education, public health improvements, and cultural enrichment that the community gains when more people attend an event at the centre. This external benefit is represented by the vertical distance between the marginal social benefits (MSB) curve and the marginal private benefit curve. The marginal social benefit represents the total benefit to the community from increasing attendance by one more person. It is the sum of the MPB and MEB representing the maximum amount of willingness to pay (MaxWTP) from the whole community, even though many community members are not participating but get external benefits for an extra person attending the centre shows. The marginal cost (MC) is the additional cost of providing the event to one more person. QM is the number of people attending without any intervention, where only private benefits are considered. It is the equilibrium point where the MPB equals the Marginal Cost.

However, Q* is the socially optimal level that considers both the private and external benefits. It is the point where the MSB equals the MC. This quantity is higher than QM, indicating that from a community perspective, it would be beneficial to increase the number of people attending beyond what the private market would provide. $Px represents the price per unit at QM. The gap between QM and Q* represents a failure; specifically, the positive externality is not captured in full. The analysis suggests that some form of intervention, like a subsidy or public provision, could be used to increase the number of people attending from QM to Q* to achieve the maximum social welfare. In addition, since the people who are excluded from attending the arts event are most likely low-income families that have a low MaxWTP due to their low income, the subsidy will increase attendance to shows and become a more inclusive provision of arts by attracting people from various socioeconomic statuses.

Performing Arts

The potential positive externalities of the performing arts for the communities and performing arts centre itself. The arts make society and communities more culturally empathetic and allow people to immerse themselves in a rich understanding of many different viewpoints and cultures. Radbourne et al. (2009) illuminate how the arts bring a combined response drawing from emotions, senses, and imagination (p. 18). This invoked a physical reaction and allowed the audience to immerse themselves in the experience. It allowed people to awaken their cognitive development and enjoy their experience. The performance arts create a better life, allowing them to appreciate the fine arts while building a culturally empathetic community. Radbourne et al. (2009) demonstrate how the performance arts create ‘collective engagement’ in which the audience members are engaged with the performers and discuss the performance with other audience members (p. 21). This showcases how a rich discussion allows the audience to interact and listen to each other and gain knowledge from others. Performance arts take risks and break down barriers that engage people to be enthralled fully and trigger their cognitive abilities. Hence, providing a subsidy will bring in low-income families that can enjoy these rich experiences.

What strategies does the city plan to implement to make the performing arts centre a more accessible and inclusive environment?

“There is a program called Jumpstart to help low-income families to help their kids get into the hockey team. For any kind of community recreation, all the policies are subsidized. The arts can be subsidized in the arts such as activity guides, more focused on acts. Other cultures have subsidized the arts better. Why is there not one for the performing arts centre? I have learned that there needs to be a kinder gentler society. There is a calmness that comes from the performing arts centre, having this facility of nurturing this. You do not know what you’re missing until you have it. Having the performance arts will allow people to be exposed to more cultural entities.”

and

“The celebration of Indigenous culture is a must. The inclusivity in terms of access, the opportunity to be more open for the LGTBQ inclusivity”

— Ken Christian, Former Kamloops Mayor (K. Christian, personal communication, March 26, 2024)

Ong and Deanne (2022) illustrate a case study of how the arts positively impacted Malaysia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) reviewed over 900 publications, analyzing over 4,000 studies that show positive externalities of arts in promoting health and preventing illness (Ong & Deanne, 2022). This showcases how the arts are a powerful visual tool to promote and communicate important messages to the public. The arts utilize aesthetic engagement, such as the imagination, promoting emotional and cognitive stimulation. The pandemic created intense social isolation that made many individuals feel depressed and negatively impacted their mental health. The arts include social interaction and physical activity, which stimulate psychological, social, and behavioural responses between the audience and performers. Ong and Deanne’s (2022) research showcases that the health outcomes are better quality of life and psychological well-being and thus lower healthcare costs which accrue to the community at large.

Effectiveness of Philanthropists for the Performing Arts Centre

Philanthropists devote their time, energy, and monetary funds as donations to help create a better life for people. Liu and Baker (2016) illustrate how philanthropists are perceived as moral and ethical leaders who are concerned with helping others with no personal rewards (p. 262). The non-profit arts and culture sector in Canada relies on public, private, and earned revenues (Trent, 2019). The public funders rely on strict rules regarding public accountability, making sure there is fair and inclusive access to public funds (Trent, 2019). This showcases how philanthropy fills the gap by providing funds and access to opportunities. The foundations, in return, take risks by investing in the projects and helping create the model within their vision. In Kamloops, there is a wide range of approaches to decolonization and addressing issues of accessibility, equity, reconciliation, and inclusiveness.

The celebration of Indigenous culture is a must. The inclusivity in terms of access, the opportunity to be more open for the LGTBQIA+ inclusivity. Trent (2019) demonstrates how Canadian philanthropists are turning their attention to consider their equity-seeking and Indigenous communities and helping them with their needs in the world. The performance arts centre in Kamloops would create a platform for the Indigenous communities to break down barriers, tell their stories, and enrich the communities’ culture through their storytelling and music. It will cultivate inclusiveness and cultural empathy and allow philanthropists to open doors for many individuals and receive a good name in return.

Philanthropists in Kamloops

Philanthropy itself can be viewed as a gift, and there are a few important philanthropists here in Kamloops, including Ron Fawcett, Dr. Ken Lepin, Law of Foundation BC, and Patricia Wolfram Selmer. Research shows how performing arts centres are most successful when philanthropists are more invested in the art creation and performing side than the building. For example, Sperling and Hall (2007) illuminated how philanthropists play a crucial role in constructing successful performing arts centres. For example, the Vancouver Opera had a dedicated supporter of the arts, Martha Lou Henley, who donated funds and their time to the opera (p. 13). Furthermore, the art philanthropist Roger Moore was also a dedicated supporter and was recognized for his time and investment in living artists (p. 13). He provided jobs and allowed dedicated time and space for creatives to explore their process and learn from each other. The Kamloops Performing Arts Centre can benefit from philanthropists’ donations to help fund the project and alleviate cost pressures.

Former Kamloops Mayor Ken Christian is very active in the campaign — the politician can see the private sector contributing to the performing arts centre (K. Christian, personal communication, March 26, 2024). There is a cost-share that appeals to people’s economy. The private sector will push it over the top, and he wants to see more of a showcase and make a statement in Kamloops. The virtue of the architecture and seeing the building is an important statement. According to Christian, putting it into a warehouse will not be in the best interest of the project. It will be a tourist attraction. In terms of affordability, the city will get grants from the provincial and federal governments.

What are the anticipated costs of constructing and maintaining the performance arts centre? How does the city plan to fund these expenses?

“The performing arts centre is going to be $74 million, utilizing philanthropic donations and tax, to be able to offset the operating costs. Ron Fawcett donated 10 million dollars, to help with the funds. Air Canada, and West Jet, Kruger, High Valley Copper can be philanthropists. It is the commitment from the people who donate and smaller contributions from people who believe in the project.”

— Ken Christian, Former Kamloops Mayor (K. Christian, personal communication, March 26, 2024)

Encapsulation of Ken Christian’s Viewpoint

Overall, Christian, had unique and informative insights into the importance of having a performing arts centre in Kamloops (personal communication, March 26, 2024). He envisions the performing arts centre will enhance the city’s cultural landscape and overall quality of life for the citizens of Kamloops. He envisions that the performing arts centre encapsulates a sense of calmness, empathy, and kindness and that the performing arts centre will nurture this. Despite previous setbacks with the referendum in 2020, with polls showing a rejection of 70-30 and the economic uncertainty from the pandemic, the performing arts centre plan did not progress. Christian illustrates that since post-pandemic economic levels have settled, the performing arts centre plans have changed designs, the security of location has improved, and a more efficient financing system is in place. A generous philanthropist, Ron Fawcett, has donated ten million dollars to help fund the performing arts centre. Many internal and external stakeholders will be able to help with the funds, but it is a commitment for those who only believe in the project.

Christian illuminates that just as sports are beloved in Kamloops, the performing arts centre will touch those who love the fine arts. It’ll be able to provide employment opportunities and give people the opportunity to see themselves in this profession. It’ll be a tourist attraction celebrating and exposing individuals to many cultural entities and allowing a space for creativity to grow. In summary, the former Mayor views the performing arts centre as playing a significant role in enhancing the quality of life for Kamloops residents, similar to the role of sports facilities. There is an acknowledgment that there has been underinvestment in the cultural sector, particularly in the performing arts, and are being taken to address this.

- Motivation for Approval — Changes in design, improved security, better financing, and pandemic-driven cultural needs helped gain approval for the performing arts centre after previous referendum rejections.

- Economic Contribution — The centre is expected to boost the local economy by attracting visitors and creating jobs, serving as a regional hub for professional development in the arts.

- Attraction for Professionals — While amenities like golf courses may be more influential, the fully booked Sagebrush Theatre indicates strong local demand for arts spaces.

- Funding and Costs — The performing arts centre will cost $74 million, funded through donations, taxes, and potential government grants, emphasizing significant private sector involvement.

- Accessibility and Inclusion — Plans are in place to ensure the centre is accessible to all, with special programs for Indigenous and LGBTQ communities and efforts similar to sports subsidies for low-income families.

- Support for Low-Income Access — The centre will offer ticket subsidies and partnerships with organizations like Big Brother to make arts accessible to low-income individuals.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the journey toward building a performing arts centre in Kamloops will illuminate the city’s commitment to cultural enrichment and community development. The research analysis of socioeconomic and political factors and the role of key stakeholders showcases the performing arts centre will provide positive benefits in the present and future for Kamloops. The decision to approve the architectural plan and allocate resources for the performing arts centre acknowledges the importance of nurturing cultural richness in the city. The positive externalities of the performing arts centre recognize the barriers to accessibility and promote equity, inclusion, and cultural diversity. Former Mayor Ken Christian’s vision for the centre is an inspirational space of cultural empathy, inclusivity, and diversity where members of the public can grow and appreciate creativity. The role of philanthropy illustrates this vision, with financial contributions from philanthropists such as Ron Fawcett illuminating the power of community investment in the arts. Philanthropists not only provide financial support but also embody the commitment to fostering creativity and social inspiration within Kamloops.

Media Attributions

Figure 1: “The demand for a hypothetical performance arts show” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 2: “Sam Noor’s poster presentation at the 190th Undergraduate Research Conference during March 2024” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Ardyanto, D., & Rachman, A. (2022). Virtual Keroncong music performances as an effort to maintain their existence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Jurnal Seni Musik, 11(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.15294/jsm.v11i1.58066

Daybreak Kamloops. (2015, November 9). Kamloops votes ‘no’ to performing arts centre complex. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/kamloops-performing-centre-1.3311017

Holliday, K. (2024a, February 6). Kamloops city council approves $7M for performing arts centre design work. Castanet. https://www.castanetkamloops.net/news/Kamloops/471086/Kamloops-city-council-approves-7M-for-performing-arts-centre-design-work

Holliday, K. (2024b, August 22). How the TCC came to be: Building the tournament capital: Historic referendum’s lasting legacy. Castanet. https://www.castanet.net/news/Kamloops/502479/BUILDING-THE-TOURNAMENT-CAPITAL-Historic-referendum-s-lasting-legacy

Kamloops This Week. (2015, April 21). Performing-arts centre: Comparing operating costs. https://archive.kamloopsthisweek.com/2015/04/21/performing-arts-centre-comparing-operating-costs/

Kim, J., & Jung, S-h. (2015). Study on CEO characteristics for management of public art performance centers. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 1(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40852-015-0007-7

Let’s Talk Kamloops (n.d.). Kamloops centre for the arts. City of Kamloops. https://letstalk.kamloops.ca/KCA

Liu, H., & Baker, C. (2016). Ordinary aristocrats: The discursive construction of philanthropists as ethical leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 133(2), 261–277. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24703691

Ong, C. Y., & Deanna, L. W. C. (2022). Emerging stronger from COVID-19 through arts. Global Health Promotion, 30(2), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/17579759221118256

Pashkus, M., Pashkus, V., & Koltsova, A. (2021). Impact of strong global brands of cultural institutions on the effective development of regions in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. SHS Web of Conferences, 92, Article No. 01039. https://doi.org/10.1051/shsconf/20219201039

Peters, J. (2024, February 6). Kamloops council approves $7M detailed design for the performing arts centre. CFJC Today. https://cfjctoday.com/2024/02/06/kamloops-council-approves-7m-detailed-design-for-performing-arts-centre/

Petruk, T. (2023, April 5). Performing arts centre plans, potential referendum discussed with federal minister. Castanet Kamloops.net. https://www.castanetkamloops.net/news/Kamloops/419587/Performing-arts-centre-plans-potential-referendum-discussed-with-federal-minister

Radbourne, J., Johanson, K., Glow, H., & White, T. (2009). The audience experience: Measuring quality in the performing arts. International Journal of Arts Management, 11(3), 16–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41064995

Rothenburger, M. (2024a, July 30). Why I believe in the PAC in spite of ‘alternative approval.’ Armchair Mayor. https://armchairmayor.ca/2024/07/30/rothenburger-why-i-believe-in-the-pac-in-spite-of-alternative-approval/

Rothenburger, M. (2024b, September 23). Alternative approval – ‘No’ effort falls short, PAC, iceplex get green light. Armchair Mayor. https://armchairmayor.ca/2024/09/23/alternative-approval-no-effort-falls-short-pac-iceplex-get-green-light/

Rothenburger, M. (2024c, September 23). Editorial – Regardless of how we got there, we’ll be glad about it. Armchair Mayor. https://armchairmayor.ca/2024/09/23/editorial-regardless-of-how-we-got-there-well-be-glad-about-it/

Rapp, K. (2001). The role of the arts in economic development. NGA Center for Best Practices. https://nasaa-arts.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Role-of-Arts-in-Economic-Development2001.pdf

Reynolds, D. (2015, November 2). Why opponents want you to vote ‘no’ for the performing arts centre. INFOnews. https://infotel.ca/newsitem/why-opponents-want-you-to-vote-no-for-the-performing-arts-centre/it24634

Schulze, A. (2022, August 9). Kamloops centre for the arts referendum won’t be on the municipal election ballot. CFJC Today. https://cfjctoday.com/2022/08/09/kamloops-centre-for-the-arts-referendum-wont-be-on-the-municipal-election-ballot/

Shepherd, L., O’Carroll, R. E., & Ferguson, E. (2014). An international comparison of deceased and living organ donation/transplant rates in opt-in and opt-out systems: a panel study. BMC Medicine, 12, 131. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-014-0131-4

Sperling, J., & Hall, M. H. (2007). Philanthropic success stories in Canada. Imagine Canada. https://sectorsource.ca/sites/default/files/resources/files/philanthropic_success_sept_2007.pdf

Trent, M. (2019, November 11). A leading role: How philanthropy can support arts and culture in Canada. The Philanthropist Journal. https://thephilanthropist.ca/2019/11/a-leading-role-how-philanthropy-can-support-arts-and-culture-in-canada/