6 Surviving the Streets: Unpacking the Economics of Homelessness

Garima Mehta

Abstract

This chapter examines the significant issue of homelessness in Kamloops by utilizing primary and secondary data to offer a comprehensive understanding of the current situation and recommend solutions to the crises the community faces. It analyzes trends and demographics related to homelessness. A framework is constructed to illustrate the pathways through which individuals enter and exit the homeless community. The framework allows us to look at the problem holistically and arrive at short and long-term solutions. Additionally, the research evaluates government programs and policies aimed at addressing homelessness, determining their effectiveness by examining the inflows and outflows within the homelessness model. Furthermore, the study assesses the importance of community involvement, non-profit organizations, and government interventions in tackling homelessness. It discusses challenges such as insufficient funding and structural barriers. Additionally, the paper explores the impact of cultural stigma and societal beliefs on socioeconomic status and homelessness. Overall, the research highlights the necessity for collaboration among various organizations to effectively address the homelessness issue in Kamloops.

Introduction

Home is not a place, it is a feeling. Those who can associate with that saying have the privilege of a stable and secure roof over their heads while being able to life live and not surviving it. Not everyone is blessed with the life circumstances resulting in secure housing. Homelessness is a pervasive issue that exists in the shadows of bustling cityscapes and among the tranquil corners of suburban neighbourhoods. Homelessness isn’t solely about lacking a physical home; it is determined by a combination of societal, economic, and personal elements. It symbolizes broader issues of inequality within society and the difficulties individuals face.

This paper attempts to search into the depths of understanding homelessness, examining its root causes, its diverse manifestations, and the various strategies employed to address it. This chapter aims to shed light on this often misunderstood and overlooked aspect of modern society through a synthesis of empirical research, policy analysis, and firsthand narratives. In the following sections, we will explore the complexities of homelessness, the structural inequities that underpin its prevalence, the challenges faced by those experiencing it, and the interventions proposed to alleviate its burden. By fostering a deeper understanding of homelessness, the ambition is to inform and inspire action and empathy in the pursuit of a more just and compassionate society. As we embark on this journey of exploration, let us remember that behind every statistic lies a human story, behind every policy debate, a person in need. It is our collective responsibility to confront the issue of homelessness with empathy, insight, and a steadfast commitment to meaningful change.

Understanding Homelessness

It is vital to begin by understanding the term ‘homeless’ and the situations it encompasses when addressing this issue. The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness provides a widely accepted definition, stating it as “the situation of an individual, family or community without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it” (Gaetz et al., 2017). Kamloops and other communities across Canada conduct a Point-in-Time Count that provides a snapshot of the number of people experiencing homelessness within a community in a 24-hour period. For this purpose, the definition is further refined to be, “an individual who does not have a place of their own where they can stay for more than 30 days, as well as if they do not pay rent,” (City Of Kamloops, 2023).

Four Main Types of Homelessness

Homelessness encompasses diverse experiences, affecting different groups in various ways. It is not voluntary, and its roots extend beyond housing instability, intertwining with societal, structural, and individual challenges such as unemployment, discrimination, domestic abuse, mental health issues, and addiction (Dionne et al., 2023). Despite its complexity, episodes of homelessness can generally be categorized into four main types: unsheltered, emergency sheltered, provisionally accommodated, and at risk of homelessness (Dionne et al., 2023).

Unsheltered homelessness involves living without consent in public or private spaces unfit for permanent habitation. Emergency-sheltered homelessness encompasses temporary accommodation in shelters for those without homes or at risk, including shelters for domestic violence victims or disaster victims. Provisionally-accommodated homelessness, commonly referred to as hidden homelessness, includes transitional housing, temporary stays with friends/family, living in hotels/motels, institutional care, or staying in facilities for recent immigrants/refugees. Those at risk of homelessness, although not currently unhoused, face imminent risks due to factors like unemployment or domestic violence, or they live in precariously housed situations, spending a significant portion of their income on housing or living in inadequate conditions (Dionne et al., 2023). The occurrence of events like eviction, job loss, or severe illness can act as tipping points that push individuals into homelessness, especially when they have depleted their resources or lack community support (Lee et al., 2021). These circumstances emphasize how homelessness often results from a combination of unfortunate events occurring in the absence of effective, preventive social insurance (Lee et al., 2021). This highlights the importance of preventative measures that need to be employed along with strategies to help those already unhoused.

Nature of Homelessness

In addition to the previous categories, special attention needs to be paid to the episodic nature of homelessness. Homelessness episodes are categorized into chronic, cyclical, or temporary types based on their duration. Chronic homelessness involves long-term or repeated episodes. Individuals must have “spent a total of at least six months (180 days) as homeless over the past year or have had recurrent episodes in the past three years with a cumulative duration of at least 18 months staying in unsheltered locations, in emergency shelters, or staying temporarily with friends or family members” (Dionne et al., 2023). Cyclical or episodic homelessness refers to periods of moving in and out of homelessness due to changing circumstances like release from institutions, changes in employment or family dynamics, income loss, or unexpected housing changes. Temporary homelessness encompasses short, isolated episodes resulting from events such as natural disasters, sudden housing changes, or house fires (Dionne et al., 2023).

Indigenous homelessness, deeply rooted in colonization and trauma, goes beyond physical homelessness to encompass a lack of a meaningful home or identity (City of Kamloops, 2023). Addressing these distinctions is crucial in understanding and tackling homelessness challenges faced by Indigenous communities in Canada.

The Housing Continuum Model

It is useful to look at the different housing types using the CMHC framework in Figure 1 to define homelessness.

This model illustrates the progression of housing needs from homelessness to market home ownership, depicting the variety of affordable housing options available in Canada for individuals lacking the financial means to access the housing market (Dionne et al., 2023). It aims to demonstrate the diversity and fluidity of housing circumstances that distinguish individuals facing homelessness from the general population (Dionne et al., 2023).

The housing continuum model presents eight categories of housing needs, ranging from less secure and shorter tenures to more secure and longer tenures. These categories are not strictly linear and may overlap. They include Homeless, Emergency Shelter, Transitional Housing, Social Housing, Affordable Rental Housing, Affordable Home Ownership, Market Rental Housing, and Market Home Ownership. There is no clear and rigid boundary that separates people who are securely housed and those who are not. Many people in Canada live in a wide, grey area between these extremes. They move within a continuum of housing options that include couch surfing, the use of homeless shelters, transitional housing and, if fortunate, low-priced rental accommodations. The common denominator for the largest part of this population is an income that is low relative to the cost of maintaining secure housing. Being Indigenous is also an important predictor of what one’s experience with homelessness will be.

Background of the Unhoused in Kamloops

The Point-in-Time Count report by the City of Kamloops (2023) is one of the only resources available to gain insights into the dynamics and demographics of the unhoused population in Kamloops. This Point-in-Time Count offers insight into the extent of homelessness on a specific day, serving as a baseline for understanding the visible and often highly vulnerable homeless population. Data was collected from eight shelters and through surveys conducted across different locations in the community (City of Kamloops, 2023). However, a 24-hour period is understandably not sufficient to provide accurate insights into the number of those unhoused and the other components studied, and hence, this report should be considered alongside other data sources for a comprehensive understanding of homelessness in the community. To begin with, between April 12 and 13, 2023, 312 individuals experienced homelessness (City of Kamloops, 2023). The data indicates a 51% increase in homelessness from 2021 and a surge of over 200% in the count of individuals identified as unhoused during Point-in-Time Counts over the last nine years (City of Kamloops, 2023).

Four Demographic Profiles

The Point-in-Time Count by the City of Kamloops (2023) also analyzes the survey data to better understand the groups of individuals comprising the homeless population in the city and the potential factors influencing the rise of homelessness locally. Four distinct groups surfaced that require focused policy interventions.

A substantial portion of respondents, representing more than half, consists of young adults who encountered homelessness during their formative years, with an average age of onset at 18 and current age averaging 34 (City of Kamloops, 2023). Nearly half of this group has familial ties to the residential school system (City of Kamloops, 2023). The gender distribution within this cohort is relatively balanced (City of Kamloops, 2023). Their average duration of homelessness exceeds three years since their initial experience, with approximately nine months of unhoused living within the past year (City of Kamloops, 2023).

A secondary group comprises approximately 25% of middle-aged females who recently experienced homelessness, typically at the age of 39, now averaging 45 years old. Their housing instability predominantly stems from financial difficulties (City of Kamloops, 2023). In contrast, about 15% of respondents are older adults who have recently become homeless for the first time in the last 3–5 years (City of Kamloops, 2023).

Lastly, a minority, constituting 10%, consists of older males who endured a troubled youth, entering homelessness around the age of 16–17 (City of Kamloops, 2023). Now averaging 55 years old, this group faces chronic homelessness, indicative of a persistent cycle often initiated in early life (City of Kamloops, 2023).

A special note needs to be made for the 6% of the homeless population that are veterans and indicated that they had served in the Canadian Forces (City of Kamloops, 2023). Veterans experiencing homelessness issue is attributed to “the difficulty in transitioning to civilian life after returning from service” (Amon & McRae, 2021).

Critical Policy Attention Areas

This data reinforces three critical areas for policy attention. Firstly, it highlights the prevalence of youth homelessness and its potential link to long-term housing instability, particularly evident in Profiles 1 and 4 (City of Kamloops, 2023). Notably, a significant proportion of youth experiencing homelessness have also been involved in the foster care system (City of Kamloops, 2023). This emphasizes the need for comprehensive support services so the unhoused can successfully obtain secure housing and preventative measures targeting the vulnerable youth demographic. Secondly, the impact of historical trauma, particularly from the residential school system, is evident, with Indigenous Peoples disproportionately represented, notably in Profile 1 (City of Kamloops, 2023). This emphasizes the need for culturally sensitive approaches to address the enduring repercussions of colonization. Lastly, the evolving nature of homelessness, influenced by housing shortages and economic uncertainties, disproportionately affects women and youth (City of Kamloops, 2023). Although women historically experienced hidden homelessness, there is a noticeable rise in instances of later-life homelessness, as seen in Profile 2, necessitating strategies to address hidden homelessness and mitigate its escalation (City of Kamloops, 2023).

Long-Term Homelessness

In analyzing the demographics and dynamics of homelessness in Kamloops, it is evident that a majority of respondents, comprising 59%, have either been long-term residents of the city or have resided there for five years or more (City of Kamloops, 2023). Notably, there has been a significant decrease in newcomers, with only 10% arriving within the past year, compared to 24% in the previous survey conducted in 2021 (City of Kamloops, 2023). Concurrently, there has been a rise in the number of individuals experiencing homelessness for durations ranging from one to five years, increasing from 20% to 31% (City of Kamloops, 2023). This shift may partly stem from individuals who arrived in 2021 or earlier and continue to face housing instability (City of Kamloops, 2023). This highlights the pressing need for sustainable, longer-term housing solutions to address persistent homelessness in the community.

Homeless Individual Relocation

Moreover, insights into the relocation patterns of homeless individuals reveal various factors influencing their migration to Kamloops. A new inquiry in the 2023 survey examines whether respondents were evacuated from their home communities, with 6% indicating that evacuation was their primary reason for relocating to Kamloops (City of Kamloops, 2023). When asked about reasons for staying, predominant factors include a lack of means to return home due to transportation constraints (80%), the presence of friends or family in Kamloops (80%), and the absence of housing options in their home communities (70%) (City of Kamloops, 2023). These findings clarify the complex interplay of social networks, economic constraints, and environmental factors shaping homelessness dynamics in Kamloops.

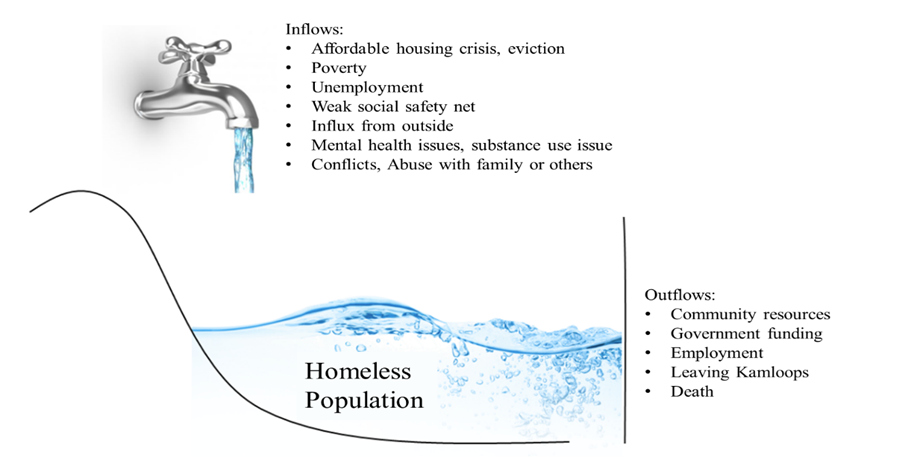

The Bathtub Model

The bathtub model is very useful in illustrating the pathways through which individuals enter and exit the homeless community. It will help us better understand the factors that push people into precarious housing situations and how to best target them before they enter the bathtub. It will also provide solutions to help those already in the bathtub.

As stated earlier, there has been an increase in 2023 homelessness by 51% relative to 2021 and over 200% over the last nine years as unhoused during Point-in-Time Counts. This means that the inflows exceeded the outflows, and the water in the bathtub was rising during this decade. However, over time inflows will fall towards the outflows, eventually reaching a long-run equilibrium whereby the homeless population will be higher with the outflows equaling the inflows into the pool. To reduce the size of the homeless population the inflows will have to decrease and the outflows increase. The focus of policy-makers has been looking at increasing the outflows through increased community resources, government funding, retraining and re-employment; however, it has been very difficult to reduce the inflows via policies and regulations such as creating affordable housing and strengthening our social safety net. In what follows, we expand on the causes and factors of homelessness in terms of inflows and outflows.

Inflows — Causes & Factors of Homelessness

Those at risk of homelessness are those who are at the tipping point, or the razor edge, of entering the homelessness pool and need particular attention to reduce the risks through policies. The causes of those at risk of homelessness are a combination of structural factors, systems failures, and individual circumstances. There is no one cause of homelessness, and there are typically compounding factors (Gaetz et al., 2016). People and families facing homelessness often have little in common except for their extreme vulnerability and insufficient access to housing, income, and the necessary support systems to maintain stable housing (“Causes of homelessness,” n.d).

Structural Factors

Structural factors encompass economic and societal issues that impact individuals’ opportunities and social conditions (“Causes of homelessness,” n.d). These factors may include insufficient income, limited access to affordable housing and healthcare, and experiences of discrimination. Changes in the national and local economy can pose challenges for individuals to secure sufficient income and afford necessities, such as food and housing.

Population Increase

Understanding the population growth in Canada, British Columbia, and smaller municipalities like Kamloops is crucial to understanding the potential impact on homelessness (Presley, 2022). Population growth places upward pressure on demands for housing, especially in areas with limited housing options. Canada experienced an 18% population increase from 2005 to 2020, with a significant portion aged between 15 and 64 years. British Columbia saw a 23% growth during the same period, with notable migration patterns contributing to its population surge. Ensuring sufficient affordable housing is available becomes imperative to mitigate homelessness risks stemming from population growth.

Income

Between 2005 and 2018, the median income for economic families and individuals not in economic families in Canada and British Columbia experienced moderate growth, increasing by approximately 25% and 24.5%, respectively (Presley, 2022). However, individuals not in economic families typically face greater challenges in accessing affordable housing due to their lower median income compared to economic families. Moreover, despite these income increases, the minimum wage in British Columbia has failed to keep pace with the rising cost of living, often forcing individuals to allocate more than 30% of their income toward housing expenses. This disparity between income and housing costs highlights the pressing need for policies that address income disparities to alleviate issues such as housing affordability, poverty, and homelessness.

Housing

In the 1990s, the Canadian government implemented substantial cuts to affordable housing programs, resulting in a decrease in available affordable housing and a significant rise in homelessness nationwide (Presley, 2022). During this time, the rental housing supply across Canada diminished as condominiums became more prevalent, prioritizing homeownership over rental options. These changes reduced the availability of housing for low-income individuals throughout the country, elevating the risk of homelessness.

Canada has not only experienced a decline in affordable, government-funded housing programs in recent decades but has also seen a surge in rental and housing prices in the private sector, surpassing the growth in household income (Presley, 2022). According to research by Dashora et al. (2018), there is a pressing need for supportive housing for those experiencing homelessness, a need that continues to escalate annually. Additionally, the lack of accessible affordable housing, coupled with limited housing options, has directly contributed to the increasing rates of homelessness across Canada.

Policy

Policy plays a crucial role in addressing housing and homelessness issues, impacting the availability of services and resources for vulnerable populations. In Canada, federal policies have shifted towards promoting homeownership and privatizing affordable housing, leading to a rise in homelessness (Presley, 2022). Provincially, British Columbia aims to ensure access to affordable housing through policy and programs, but income assistance rates have not kept pace with rising housing costs. Overall, the disconnect between income and housing costs remains a significant challenge, contributing to homelessness and financial struggles across the province.

Systems Failures

Systems failures happen when various systems intended to provide care and support fail to meet the needs of vulnerable individuals, leading them to seek assistance from the homelessness sector (“Causes of homelessness,” n.d.). Instances of systems failures include challenging transitions from child welfare services, inadequate support for immigrants and refugees, and insufficient planning for individuals being discharged from hospitals, correctional facilities, and mental health or addiction treatment centres (“Causes of homelessness,” n.d.).

Foster Care System

In the City of Kamloops (2023) Point-in-Time Count, 35% (60 individuals) acknowledged being involved in the foster care system, marking a decrease from 2021, when 50% (70 individuals) reported being part of the foster care system during their youth. Among those who encountered homelessness during their youth, 43% also had experience with foster care. This emphasizes the need for distinct prevention policies that target youth in foster care systems to ensure their smooth transition into adult life in society.

Veteran Transition to Civilian Lifestyle

Veteran homelessness is often attributed to the lack of structured transitional programs upon their return to civilian life. Many veterans express the need for comprehensive support services, including financial assistance, vocational training, mental health support, and substance abuse treatment (Amon & McRae, 2021). Studies indicate a high prevalence of addiction and mental illness among homeless veterans, with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) affecting them. The absence of adequate support structures during the transition exacerbates mental health struggles and substance abuse tendencies, perpetuating the cycle of veteran homelessness.

Personal Circumstances & Relational Problems

Individual and interpersonal factors contribute to the personal situations of individuals experiencing homelessness. These factors may encompass traumatic incidents (such as house fires or job loss), personal upheavals (such as family breakdowns or domestic violence), mental health issues (such as substance abuse), certain conditions (such as a brain injury or fetal alcohol syndrome, which can both lead to and result from homelessness), and physical health ailments or disabilities (“Causes of homelessness,” n.d.). Relational challenges may involve family violence, substance abuse, and mental health issues among other family members, as well as extreme poverty.

Abuse

The rise in family violence incidents in Canada, particularly affecting women and girls, has heightened concerns about the link between abusive home situations and homelessness (Dionne et al., 2023). Relationship issues and fleeing abuse are significant factors driving Canadians into homelessness, with women being four times more likely than men to experience homelessness due to fleeing abuse (Dionne et al., 2023). Specifically, over two in five women have faced absolute homelessness at some point because of fleeing abuse, compared to a smaller percentage of men (Dionne et al., 2023).

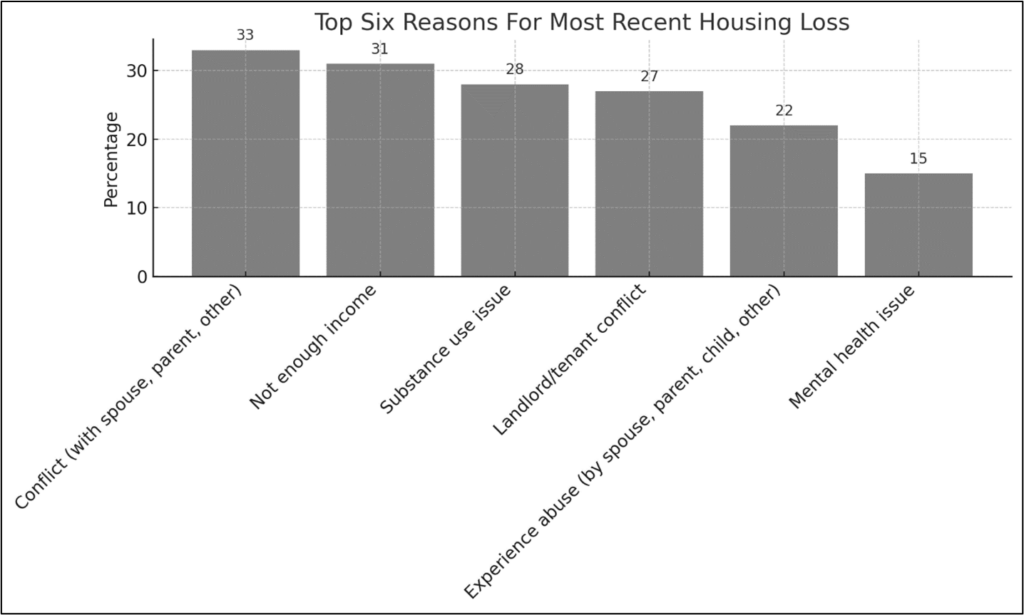

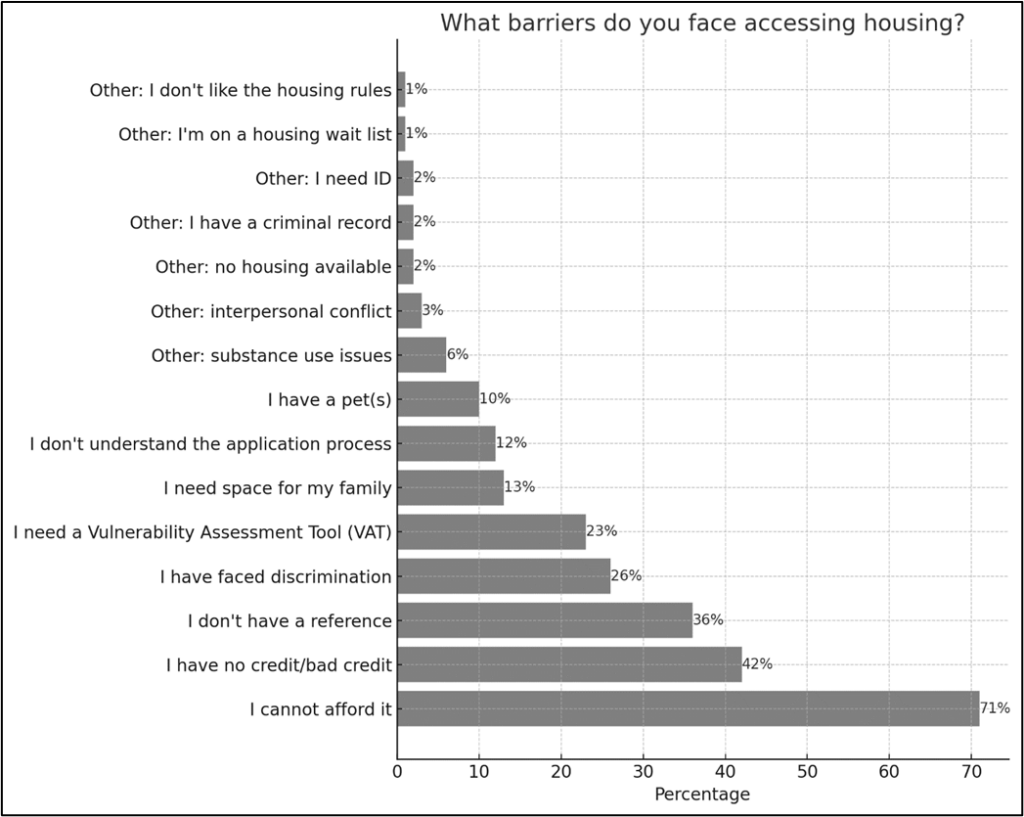

The most common causes of homelessness in Kamloops are an interplay of the above reasons. Survey respondents from the Point-in-Time Count reported their reasons for their most recent housing loss, as shown in Figure 2. Once in the bathtub of experiencing homelessness, these reasons compound further and pose challenges and barriers to accessing housing and exiting the bathtub. Survey respondents’ data for persisting homeless experience is shown in Figure 3.

Potential Inflows — Low-Income Families in Kamloops

The low-income cut-offs, after tax (LICO-AT) is a poverty threshold measure designed to identify individuals and families whose expenditure on necessities — food, shelter, and clothing — significantly exceeds the average proportion by 20 percentage points, thus indicating a higher economic burden. This measure is calculated based on detailed household expenditure data, allowing it to reflect the direct impact of necessary spending on overall financial well-being. LICO-AT values are also adjusted according to the size of the household and the population size of the area in which the household resides, capturing the variance in the cost of living between different regions and community sizes (Statistics Canada, 2024). For example, the LICO-AT for communities with a population of 100,000 to 499,999 and a family size of 4 persons would be $38,930 in 2022. LICO-AT can thus assess the risk of economic hardships and that of becoming homeless. By highlighting households that are under significant financial strain due to essential expenses, LICO-AT not only helps identify families at high risk of housing instability but also serves as a crucial determinant for eligibility in various social assistance programs aimed at mitigating poverty and preventing homelessness.

In 2021, Canadian households faced significant expenses across shelter, food, and transportation. The average annual costs were approximately $15,256 for shelter among renters, $33,118 for homeowners with mortgages, $10,099 for transportation, and $8,065 for food purchased from stores (Statistics Canada, 2023b). Using these figures to estimate a LICO-AT threshold, the calculated threshold would be around $40,104 for renters and higher for homeowners with mortgages. This calculation serves as a rough indicator, suggesting that families earning less than this amount may experience financial strain significant enough to be considered low-income under the LICO-AT standard. This threshold helps in assessing the economic challenges that can impact housing stability and the potential risk of homelessness.

Table 1, using data obtained from Census Canada 2021, shows the distribution of the population by age group in Kamloops and the number of people that are at the LICO-AT threshold. There are 3,625 people experiencing hardship, and thus, some are at risk of flowing into the homeless pool. The majority are in the 18–64 age range, followed by the youngest population. There are also 215 retired people having difficulties meeting their needs. Furthermore, 8,645 people are in the bottom decile of the adjusted after-tax economic family income for the population in private households. These are the poorest in terms of income in that 90% of the families make more family income than this group. They are in the bottom 10% of all families in Kamloops and are vulnerable to ending up homeless. The moral of this story is that we need stronger social security nets to reduce the inflow of people into the homeless bathtub.

Table 1: Distribution of LICO-AT Population

| Skip Table 1A | |||

| Population Category | # of People | Families in LICO-AT | % by Age Group in LICO-AT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Population | 94,560 | 3,625 | 100.0% |

| 0 to 17 years | 17,800 | 500 | 13.8% |

| 0 to 5 years | 5,430 | 130 | 3.6% |

| 18 to 64 years | 59,085 | 2,915 | 80.4% |

| 65 years and over | 17,670 | 215 | 5.9% |

| Skip Table 1B | ||

| Category | # of People | % of People Relative to Total Population |

|---|---|---|

| Families in LICO-AT | 3,625 | 3.8% |

| Bottom Decile of the Adjusted After-Tax Economic Family Income for the Population in Private Households | 8,645 | 9.1% |

Note. Data for Table 16A and 16B from Statistics Canada (2023b).

The Health of the Homeless

So far, we have understood the complexities of homeless experiences and the multifaceted reasons that one may encounter such issues. Undoubtedly, losing the security and comfort of a house undoubtedly creates harsh conditions for individuals to survive in their day-to-day lives. It also makes them more prone to health challenges and substance use issues. It is essential to recognize that homelessness is not solely caused by substance use; instead, it is a multifaceted issue influenced by socioeconomic factors. Housing instability, often due to low income, heightens the risk of losing shelter for individuals who use substances, leading to a vicious cycle of homelessness and addiction (Homeless Hub, n.d.).

Substance Use Issues

Once on the streets, individuals facing substance use issues encounter barriers to accessing essential healthcare services, including substance use treatment and recovery support (Homeless Hub, n.d.). The lack of stable housing aggravates their vulnerability, inhibiting their ability to address underlying addiction issues effectively. Moreover, the environment of homelessness fosters a range of health risks, including deteriorating physical and mental health and accidental injuries. This is visible from the City of Kamloops (2023) Point-in-Time Count, where more than a third of respondents identified as having either a medical condition (36%) or physical disability (34%). 25% of respondents identified as having a learning disability or cognitive limitation. It is important to understand that homelessness can worsen mental health issues and substance use (Homeless Hub, n.d.). Substance use was the most commonly cited health challenge (65%), closely followed by mental health issues (49%), aligning with existing research that indicates that substance use is disproportionately higher among individuals experiencing homelessness (City of Kamloops, 2023).

Increased Health Risks

Essentially, homeless individuals experience higher rates of premature death compared to those with stable housing, primarily due to factors such as injuries, accidental overdoses, and exposure to extreme weather conditions (Galea, 2016). A study on Canada’s homelessness by Frankish et al. (2005) reports that homelessness impacts the health of individuals, with a multitude of factors contributing to increased health risks among this population. Homeless individuals are susceptible to a range of health issues, including mental illness, substance abuse, infectious diseases, such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, injuries from assaults, chronic medical conditions, and poor oral health (Frankish et al., 2005). They face significant barriers to accessing healthcare, often lacking health insurance, facing challenges in making and keeping appointments, and experiencing transience without a permanent address (Frankish et al., 2005). Despite high healthcare utilization rates, homeless individuals struggle to receive adequate medical care, resulting in frequent hospitalizations and prolonged stays (Frankish et al., 2005). This reports the urgent need for comprehensive support services and interventions tailored to address the complex health needs of the homeless population.

Outflows — How to End Homelessness?

The Canadian Observatory on Homelessness provides invaluable insights into the concept of ending homelessness and says that ending it goes beyond the mitigation of immediate crises; it entails a comprehensive task aimed at eradicating a pervasive social issue (“Defining end to homelessness,” n.d.). The Canadian ‘Definition of Homelessness’ offers a compelling framework, emphasizing the failure of society to provide adequate systems, funding, and support to ensure housing access for individuals, even in times of crisis that are beyond one’s control. At its core, ending homelessness entails facilitating housing stability, characterized by secure, appropriate, and supportive housing options that address individuals’ diverse needs. This paradigm shift requires a departure from the conventional reliance on emergency services towards proactive approaches that prioritize prevention and interventions leading to sustainable housing outcomes.

In this context, the term ‘outflows from homelessness’ encapsulates the strategies and initiatives aimed at transitioning individuals from homelessness to stable housing situations. These approaches encompass rapid rehousing initiatives and permanent supportive housing programs, all geared towards ensuring that homelessness is a temporary, not a chronic, condition. By embracing innovative strategies and reshaping societal attitudes towards homelessness, communities can work towards achieving a future where no individual is left without a stable place to call home.

Gaetz et al. (2014) reported that investing in affordable housing initiatives to address homelessness is not just a moral imperative but also a financially prudent decision. They stress that by allocating resources towards providing stable housing for the most vulnerable, we can mitigate the societal costs associated with homelessness, which currently amount to billions annually. Despite initial investment concerns, the long-term benefits of reducing homelessness far outweigh the economic burden of inaction, making it a cost-effective solution for both individuals and the economy as a whole.

Housing & Support Services in Kamloops

Even if, in an ideal world, there was no chronic homelessness, there would continue to be situations that would push people into precarious circumstances like “people who must leave home because of family conflict and violence, eviction or other emergencies, as well as those who simply face challenges in making the transition to independent living” (“Defining end to homelessness,” n.d.). Therefore, we will always need some form of emergency services to support and guide people through these situations. This section discusses the different services available to ensure a roof over the heads of those facing homelessness and support to foster overall well-being and continued stability.

Emergency Shelters

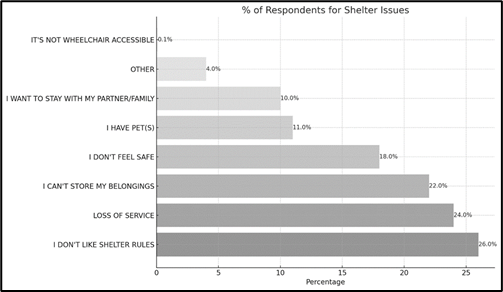

Emergency shelters in Kamloops play a crucial role as an immediate response to homelessness, offering essential necessities and a temporary refuge for individuals in need. While shelters serve as a starting point for individuals to rebuild their lives, they also serve as a vital link to connect them with resources and support services. The Point-in-Time Count report studied shelter data from April 16, 2021, to April 12, 2023, which revealed an increase in both available beds and their utilization. In 2021, there were 180 shelter beds, while in 2023, there were 202 beds. The occupancy rates also rose, with 65% in 2021 and 95% in 2023, indicating that more people experiencing homelessness were accessing shelter services during the 2023 Point-In-Time Count. However, despite the availability of shelters, there are various reasons why some individuals may not access them, as shown in Figure 5, highlighting the need for further research and improvements in shelter accessibility.

Stable Housing

Furthermore, supportive housing, transitional housing, and affordable housing programs offered by organizations like Ask Wellness, CMHA, and The Mustard Seed complement emergency shelter services by providing individuals with more stable and long-term housing solutions. Supportive housing, in particular, offers subsidized housing with on-site support for single adults, seniors, and people with disabilities, helping them find and maintain stable housing. Transitional housing programs cater to individuals who have achieved stability but still require some level of assistance as they transition to independent living. Affordable housing options provided by community resources like ASK Wellness and CMHA also play a crucial role in addressing the broader housing crisis in Kamloops. Together, these housing options form a continuum of care, allowing individuals to progress toward greater housing stability and ultimately break the cycle of homelessness.

Recovery Centres

For homeless individuals grappling with mental health challenges, substance use issues, and the looming threat of overdose, comprehensive support services are essential for their well-being and recovery journey. Recovery centres equipped with trained professionals offer a safe haven where individuals can access specialized care tailored to their needs. These centres provide a range of support services, including counselling, therapy, medication management, and peer support groups, aimed at addressing mental health issues and substance use disorders concurrently. Moreover, they implement overdose response protocols and harm reduction strategies to mitigate the risks associated with opioid use, such as providing naloxone kits and overdose prevention education. By offering a holistic approach that addresses both mental health and substance use concerns, these support services empower homeless individuals to embark on a path toward recovery and long-term stability, fostering hope and resilience in the face of adversity. Other community groups offer such services, including Interior Health, Opioid Use Disorder Resources, Kamloops Aboriginal Friendship Society, and Interior Community Services.

Interviews

Interview With ASK Wellness COO — Kim Galloway

In an insightful interview, Kim Galloway, COO of ASK Wellness, shared her insights and experiences addressing the complex issue of homelessness (K. Galloway, personal communication, May 6, 2024). Drawing from her extensive experience in the field, Galloway emphasized the critical intersections between mental illness, substance abuse, and homelessness. She noted that addressing health needs is often a prerequisite for effective housing solutions. Kim also discussed the evolution of shelter policies over the years, noting a significant shift from short-term emergency stays to more sustainable, long-term housing solutions. Historically, shelters operated on strict time limits and required residents to have a plan for their future within days. However, ASK Wellness has been at the forefront of changing this paradigm by developing diverse housing options. These include low-barrier housing, which does not require sobriety for entry, supportive recovery housing for those working towards sobriety, and transitional housing that helps individuals move from homelessness to permanent housing. This diversity allows ASK Wellness to meet the varied needs of the homeless population more effectively.

Preventative Measures

Preventive measures are another critical aspect of ASK Wellness’s strategy (K. Galloway, personal communication, May 6, 2024). Galloway underscored the importance of housing subsidies in keeping at-risk families in their homes, thus preventing homelessness before it starts. She described the organization’s efforts to provide both short-term and long-term subsidies as essential components of their preventive services. Galloway also addressed common misconceptions about low-barrier housing, particularly the stigma associated with enabling substance use. She explained that these housing options are designed to provide a stable environment where individuals can begin to address their substance use issues with the support of staff and community partners.

Success Stories

The interview highlighted several success stories that illustrate the impact of ASK Wellness’s programs (K. Galloway, personal communication, May 6, 2024). These ranged from individuals achieving sobriety and moving on to live independently to others stabilizing their mental health and reconnecting with their families. Galloway shared examples of residents who transitioned from supportive housing to living sober lifestyles, with some even gaining employment within the organization. She also recounted stories of individuals with severe mental illness who, through stable housing and consistent support, managed to rebuild their lives and re-establish relationships with loved ones.

Future of ASK Wellness

Looking ahead, Galloway outlined ASK Wellness’s ambitious plans for expansion (K. Galloway, personal communication, May 6, 2024). The organization is extending its reach to multiple cities, including Kamloops, Merritt, and Penticton. New projects are in development, such as family-specific housing and youth-specific units, which aim to address the needs of different demographic groups within the homeless population. For instance, a new family building with 80 units is expected to be ready next year, providing much-needed housing for families and older adults. Additionally, ASK Wellness is planning to enhance its supportive recovery housing in the Okanagan, offering abstinence-based living environments for those committed to sobriety.

Galloway also discussed the broader systemic challenges and the need for more integrated services (K. Galloway, personal communication, May 6, 2024). She advocated for an increase in outreach workers and portable medical services to meet individuals where they are. Galloway stressed that more resources are needed, including recovery beds, transitional housing, and low-barrier housing, to complement the efforts of outreach workers.

In conclusion, the interview with Kim Galloway provided a comprehensive overview of ASK Wellness’s multifaceted approach to addressing homelessness. By focusing on health needs, diversifying housing options, implementing preventive measures, and expanding services, ASK Wellness aims to create sustainable, community-based solutions. Galloway’s insights highlight the importance of a holistic and compassionate approach to homelessness, one that recognizes the unique needs of each individual and strives to build a caring, inclusive community.

Interview With Mayor of Kamloops — Reid Hamer-Jackson

In a recent interview, the mayor shared his extensive experience and insights gained from spending four years engaging with the homeless population in Kamloops, often in the early hours of the morning (R. Hamer-Jackson, personal communication, April 25, 2024). His primary goal is to transition people from living on the streets and beaches into housing and support programs. He highlighted the intertwined issues of homelessness, mental health, and addiction, emphasizing the necessity for comprehensive solutions beyond harm reduction. While acknowledging the importance of harm reduction facilities, the mayor stressed the need for more robust recovery programs to help individuals overcome substance abuse and reintegrate into society. Before his tenure as mayor, he was involved in efforts to establish a recovery wellness ranch, reflecting his long-standing commitment to this cause.

Treatment for Substance Use Issues

The mayor shared anecdotes about individuals struggling with substance use who aspired to turn their lives around but tragically succumbed to overdoses (R. Hamer-Jackson, personal communication, April 25, 2024). He noted that Kamloops has significant potential due to the availability of numerous buildings, such as supportive housing facilities, motels, and shelters. However, he pointed out that most of these are harm reduction-focused. He advocated for creating diverse treatment options, separating those who wish to pursue sobriety from environments where drug consumption occurs. He emphasized the need for enhanced support and wrap-around services, which are essential for effective recovery. Additionally, the mayor called for a thorough review and clear metrics to assess the long-term efficacy of harm reduction and recovery programs. He highlighted the importance of programs that facilitate the return of non-local homeless individuals to their home communities, addressing a significant portion of the homeless population in Kamloops.

Community Support & Understanding

He also stressed the need for community support and understanding, emphasizing that homeless people are also citizens deserving of empathy and assistance (R. Hamer-Jackson, personal communication, April 25, 2024). Since 2020, he has been advocating for a review of existing services and reallocation of funding towards recovery initiatives. He warned that without adequate support services to address addiction, newly-housed individuals risk repeated evictions. The mayor underscored the importance of listening to the homeless population’s stories to foster a deeper understanding and create more effective, compassionate solutions to homelessness.

New Housing Initiatives

As of the time of writing of this chapter and the research that has been gathered to date, a new housing initiative was announced by British Columbia’s Housing Minister Ravi Kahlon. There will 500 new homes and shelters built in Kamloops over the near future (Holliday, 2024). These projects will affect the inflows and outflows of the bathtub. Inflows will drop and outflows will increase from the homelessness pool controlling for all other factors. Inflows will fall due to the affordable new housing and outflows will increase due to the mission flats, shelter spaces and accommodating seniors that are in need or homeless.

The specific projects under this initiative include:

- Mission Flats Road — Two 98-unit modular housing projects to help the needy, replacing a 54-unit unit nearby.

- Shelter Spaces — Funding 100 new homeless shelters for immediate relief.

- Columbia Precinct Lands — Two 200-unit buildings near the courthouse for middle-income earners. This would help prevent homelessness.

- Lorne Street — A 40-bed-round shelter for at-risk seniors and disabled people on the brink of homelessness. As mentioned, Kamloops has a senior homeless population, and this initiative should increase outflows.

- Oak Road, North Shore — A Connective Support Society Kamloops-led general housing project with 20 new homes.

- Women’s Housing Project — A 22-unit women’s transition housing project will be built with the Kamloops and District Elizabeth Fry Society to house women and children fleeing violence. An increasingly vulnerable demographic that needs special attention.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the issue of homelessness in Kamloops, as in many other communities, is complex and multifaceted, stemming from a combination of structural, systemic, and individual factors. As explored in this paper, understanding homelessness requires a comprehensive approach that considers not only the immediate challenges faced by individuals without stable housing but also the underlying root causes that perpetuate the cycle of homelessness. From economic disparities and housing shortages to systemic failures in social services and personal crises, the pathways to homelessness are diverse and interconnected.

Furthermore, the insights gleaned from data analysis and qualitative research underscore the urgent need for sustainable, longer-term housing solutions to address persistent homelessness in the community. While emergency shelters and short-term interventions play a crucial role in providing immediate relief to those experiencing homelessness, they are not sufficient to address the underlying structural issues that perpetuate housing instability. Sustainable solutions must focus on increasing the availability of affordable housing, providing wraparound support services, and addressing systemic barriers that prevent individuals from accessing and maintaining stable housing.

Moreover, the findings highlight the importance of adopting a holistic and collaborative approach to addressing homelessness, involving multiple stakeholders, including government agencies, non-profit organizations, community groups, and individuals with lived experience. By working together to implement evidence-based policies and programs, communities can create a more supportive and inclusive environment that ensures all residents have access to safe, affordable housing and the support they need to thrive.

Moving forward, Kamloops and other communities must continue investing in supportive housing, recovery programs, and wrap-around services while also addressing systemic barriers and stigma associated with homelessness. By adopting a proactive approach that prioritizes prevention, intervention, and long-term solutions, communities can work towards ending homelessness and building a more equitable and inclusive society for all residents.

Ultimately, ending homelessness is not just a moral imperative but also a practical investment in the well-being and prosperity of communities. By providing stable housing, comprehensive support services, and opportunities for individuals to rebuild their lives, communities like Kamloops can create a brighter future where everyone has a place to call home.

Media Attributions

Figure 1: “The housing continuum” [modified from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, 2018] by Statistics Canada (2023a) is used under the Statistics Canada Open License.

Figure 2: “Top six reasons housing loss in Kamloops chart” [using data from City of Kamloops (2023)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 3: “Barriers faced when accessing housing chart” [using data from City of Kamloops (2023)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 4: “Bathtub model” [adapted from The Unemployment Bathtub Analogy by Tsigaris (2024)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 5: “Reasons for not accessing shelters chart” [using data from City of Kamloops (2023)] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Amon, E., & McRae, L. (2021, November 11). Is veteran homelessness a problem in Canada? Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/blog/veteran-homelessness-problem-canada

Causes of Homelessness. (n.d.). Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/homelessness-101/causes-homelessness

City of Kamloops. (2023). 2023 Kamloops point-in-time count report. https://www.kamloops.ca/sites/default/files/docs/2023%20Point%20In%20Time%20Count%20Final%20Report.pdf

Dashora, P., Kiaras, S., & Richter, S. (2018). Homelessness in a resource-dependent rural community: A community-based approach. Journal of Rural & Community Development, 13(3), 133–151. https://journals.brandonu.ca/jrcd/article/view/1567

Defining end to homelessness. (n.d.). Homeless Hub. Retrieved May 1, 2024, from https://www.homelesshub.ca/solutions/ending-homelessness/defining-end-homelessness

Dionne, M-A., Laporte, C., Loeppky, J., & Miller, A. (2023, June 16). A review of Canadian homelessness data, 2023. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75f0002m/75f0002m2023004-eng.htm#a1

Frankish, C. J., Hwang, S. W., & Quantz, D. (2005). Homelessness and health in Canada: Research lessons and priorities. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 96(Suppl 2), S23–S29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03403700

Gaetz, S., Dej, E., Richter, T., & Redman, M. (2016). The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC16_final_20Oct2016.pdf

Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, C., Harris, B., Hill, C., Kovacs-Burns, K., Pauly, BK., Pearce, B., Turner, A., & Marsolais, A. (2012). Canadian definition of homelessness. Canadian Observatory on Homelessness. https://www.homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/COHhomelessdefinition.pdf

Gaetz, S., Gulliver, T., & Richter, T. (2014). The state of homelessness in Canada 2014. The Homeless Hub Press. https://homelesshub.ca/sites/default/files/SOHC2014.pdf

Galea, S. (2016, February 28). Homelessness, its consequences, and its cause. Boston University School of Public Health. https://www.bu.edu/sph/news/articles/2016/homelessness-its-consequences-and-its-causes/

Holliday, K. (2024, June 24). Housing minister touts ‘game-changing’ projects in Kamloops, promises to build hundreds of homes. Castanet. https://www.castanet.net/news/Kamloops/493908/Housing-minister-touts-game-changing-projects-in-Kamloops-promises-to-build-hundreds-of-homes

Homeless Hub. (n.d.). Substance use & addiction. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/topics/substance-use-addiction

Lee, B. A., Shinn, M., & Culhane, D. P. (2021). Homelessness as a moving target. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 693(1), 8–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716221997038

Presley, B. (2022). Addressing homelessness in a smaller Canadian city: Community-engaged research with Vernon, B.C. UBC Library Open Collections. https://doi.org/10.14288/1.0413119

Substance Use & Addiction. (n.d.a). Homeless Hub. https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/topics/substance-use-addiction

Statistics Canada. (2023a). Census profile, 2021 census of population (No. 98-316-X2021001) [Table]. Government of Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Statistics Canada. (2023b). Survey of household spending, 2021. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/231018/dq231018a-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2024). Low income cut-offs (LICOs) before and after tax by community size and family size, in current dollars (No. 11-10-0241-01) [Table]. Government of Canada. https://doi.org/10.25318/1110024101-eng

Tsigaris, P. (2024). The unemployment bathtub analogy [Image]. In In the Shadow of the Hills: Socioeconomic Struggles in Kamloops. https://shadowofthehills.pressbooks.tru.ca/chapter/understanding-kamloops-neighbourhood-unemployment-rates/

Long Descriptions

Figure 1 Long Description: From left to right, the housing continuum includes homeless, emergency shelters, transitional housing, social housing, affordable rental housing, affordable home ownership, market rental housing, and market home ownership. [Return to Figure 1]

Figure 2 Long Description: The top six reasons people had for most recent housing loss include:

- Conflict (with spouse, parent, or other) — 33%

- Not enough income — 31%

- Substance use issue — 28%

- Landlord/tenant conflict — 27%

- Experience abuse (by spouse, parent, child, or other) — 22%

- Mental health issue — 15%

Figure 3 Long Description: Barriers people face when accessing housing include:

- Other: I don’t like the housing rules — 1%

- Other: I’m on a housing wait list — 1%

- Other: I need ID — 2%

- Other: I have a criminal record — 2%

- Other: No housing available — 2%

- Other: Interpersonal conflict — 3%

- Other: Substance abuse issues — 6%

- I have a pet(s) — 10%

- I don’t understand the application process — 12%

- I need space for my family — 13%

- I need a Vulnerability Assessment Tool (VAT) — 23%

- I have faced discrimination — 26%

- I don’t have a reference — 36%

- I have no credit/bad credit — 42%

- I cannot afford it — 71%

Figure 4 Long Description: Homeless population inflows include affordable housing crisis, eviction, poverty, unemployment, weak social safety net, influx from outside, mental health issues, substance use issues, conflict, and abuse from family or others. Homeless population outflows include community resources, government funding, employment, leaving Kamloops, and death. [Return to Figure 4]

Figure 5 Long Description: Reasons for not accessing shelters incldue:

- It’s not wheelchair accessible — 0.1%

- Other — 4%

- I want to stay with my partner/family — 10%

- I have pet(s) — 11%

- I don’t feel safe — 18%

- I can’t store my belongings — 22%

- Loss of service — 24%

- I don’t like shelter rules — 26%