4 Transitioning to Local Authority: Practical Steps & Challenges

Patrick Izett

Abstract

This chapter compares the economic implications of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police versus municipal police forces and examines how they might affect Kamloops’ long-term prospects. Comparative analysis and secondary data will be used to assess the economic effects of both police methods. This study looks at cost-effectiveness, community involvement, and resource sharing to consider which police plan might work best for Kamloops in the long run. Researchers have found that each police choice may have pros and cons for the city’s economy. This will help lawmakers and other interested parties make better decisions about the city’s long-term growth.

Introduction

As Kamloops considers transitioning from the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to a municipal police force, it is crucial to thoroughly analyze the socioeconomic impacts of both policing models. This chapter examines the implications of retaining the RCMP versus establishing a local police authority versus moving towards a regionalized hybrid model by evaluating key issues, such as resource allocation, crime prevention, community engagement, and cost-effectiveness. This study aims to provide better insight into making an informed decision to support the long-term prosperity of Kamloops. Building upon existing literature and utilizing a variety of primary and secondary data sources, this analysis will explore how each method of policing influences the socioeconomic outcomes in Kamloops.

Through analyzing public perception, budget trade-offs, interagency collaboration, and more, this chapter seeks to uncover the significant socioeconomic effects each policing option could offer Kamloops’ society. The goal is to not only highlight practical steps and challenges of making the transition to a municipal police department but also deliver actionable insights to policymakers, law enforcement, and stakeholders invested in the future of Kamloops. Having a better understanding of the socioeconomic implications of these policing models will allow the city to make a more informed decision that works toward improved safety and a more resilient and economically vibrant future for Kamloops and its residents.

This chapter explores the benefits of a different policing method in Kamloops, analyzing primary and secondary data and existing literature to examine its long-term prospects. It highlights the practical steps and challenges of transitioning to a new policing model that positively impacts the city. The research provides a comprehensive overview of the socioeconomic implications of employing the RCMP as a municipal police force or a hybrid model in Kamloops. The chapter also summarizes findings from sources, highlighting the pros and cons of employing the RCMP or a municipal police force. The goal is to provide practical steps and challenges to transitioning to a policing model that addresses Kamloops’ needs.

Literature Review

Studies on the RCMP and municipal police forces in Canada uncover various strategies and obstacles in crime prevention. Murphy (1998) presents alterations in well-established policing structures, ideologies, and operational practices, connecting them to changes in the economy and culture of governance and law enforcement. Griffiths (2019) emphasizes the significance of specialized units and adaptations in northern community policing. On the other hand, Demers (2019) and Slotwinski (2010) explore the diverse effects of police staffing and funding on reducing crime rates. Kitchen’s (2007) research revealed a robust correlation between crime rates and socioeconomic status in Canadian urban areas. Canadian police oversight has experienced a surge in the past decade as a result of notable instances of police misconduct and public discontent with internal police investigations. Supervision enhances the level of responsibility of the police, fosters trust from the public, and influences conduct (Stelkia, 2020).

Griffiths et al. (2014) examine the lack of utilization by Canadian police services, governments, research institutions, and other police stakeholders of the numerous opportunities for enhanced collaboration on policing research matters. With rare deviations, Canadian police services have not made significant investments in cultivating the ability to carry out policing research that emphasizes outcomes rather than outputs. According to Griffiths et al. (2014), establishing a national policing research center that is credible, comprehensive, and representative is considered essential for addressing the various challenges identified. Sytsma and Laming (2018) emphasize the obstacles and constraints involved in researching the economics of policing in Canada. In addition, how the police behave, and the level of public safety are significantly influenced by governance and institutional factors, such as judicial supervision and financial mechanisms, as highlighted by Goldstein et al. (2018) and Cyr et al. (2020).

To reduce crime effectively, a comprehensive approach that considers factors such as organizational structure, funding, community engagement, and officer well-being is necessary.

Methodology

Literature has been found using academic databases, such as Thompson Rivers University Libraries, University of British Columbia Library, Google Scholar, and JSTOR, and by conducting two interviews with police officers. Finding sources in the databases involved searching for specific keywords or terms such as “RCMP,” “municipal police,” “policing and its economic impact,” “policing models in Canada,” and “transitioning from RCMP.” Additional sources were found using citation chaining and reference lists of relevant articles. Sources found were critically evaluated for their relevance to the topic and credibility. Sources focused on the economic implications of the RCMP and municipal policing were prioritized. Finally, the two interviews focused on the perspectives of a local police officer in Kamloops and a municipal officer from B.C.’s Lower Mainland. These interviews gave insight and a better understanding of the operations of both the RCMP and municipal policing.

Furthermore, this study focused on the city of Kamloops and compared it to the cities of Delta, Saanich, and New Westminster. These additional cities were chosen due to their similar population size to Kamloops and their use of a municipal policing model. All sources used in the literature review are accurately cited and referenced according to current APA citation guidelines.

Comparing Policing & Crime in Four Cities

Under British Columbia’s Police Act (1996), the provincial government is responsible for policing and law enforcement in unincorporated and rural areas and municipalities with a population under 5,000 (Government of British Columbia, 20221). Furthermore, a city with a population of over 5,000 is responsible for providing and bearing the necessary expenses of policing and law enforcement within its municipal boundaries. These municipalities may do so by forming their municipal department and contracting the RCMP municipal police services. Kamloops is currently one of 68 municipalities that are policed by the RCMP (Government of British Columbia, 2021). In 2012, the provincial government signed a 20-year Provincial Police Service Agreement (PPSA) with the federal government to contract the RCMP as B.C.’s Provincial Police Service. Under the terms of the PPSA and the Police Act (1996), municipalities with a population of 15,000 or larger pay 90% of the cost base, with the federal government paying 10% of the cost base. These municipalities are responsible for 100% of certain costs, such as accommodation and support staff (Government of British Columbia, 2021). Thus, Kamloops pays 90% of the cost base, and the federal government contributes 10% of the cost base. The city is still responsible for additional accommodation costs and support staff.

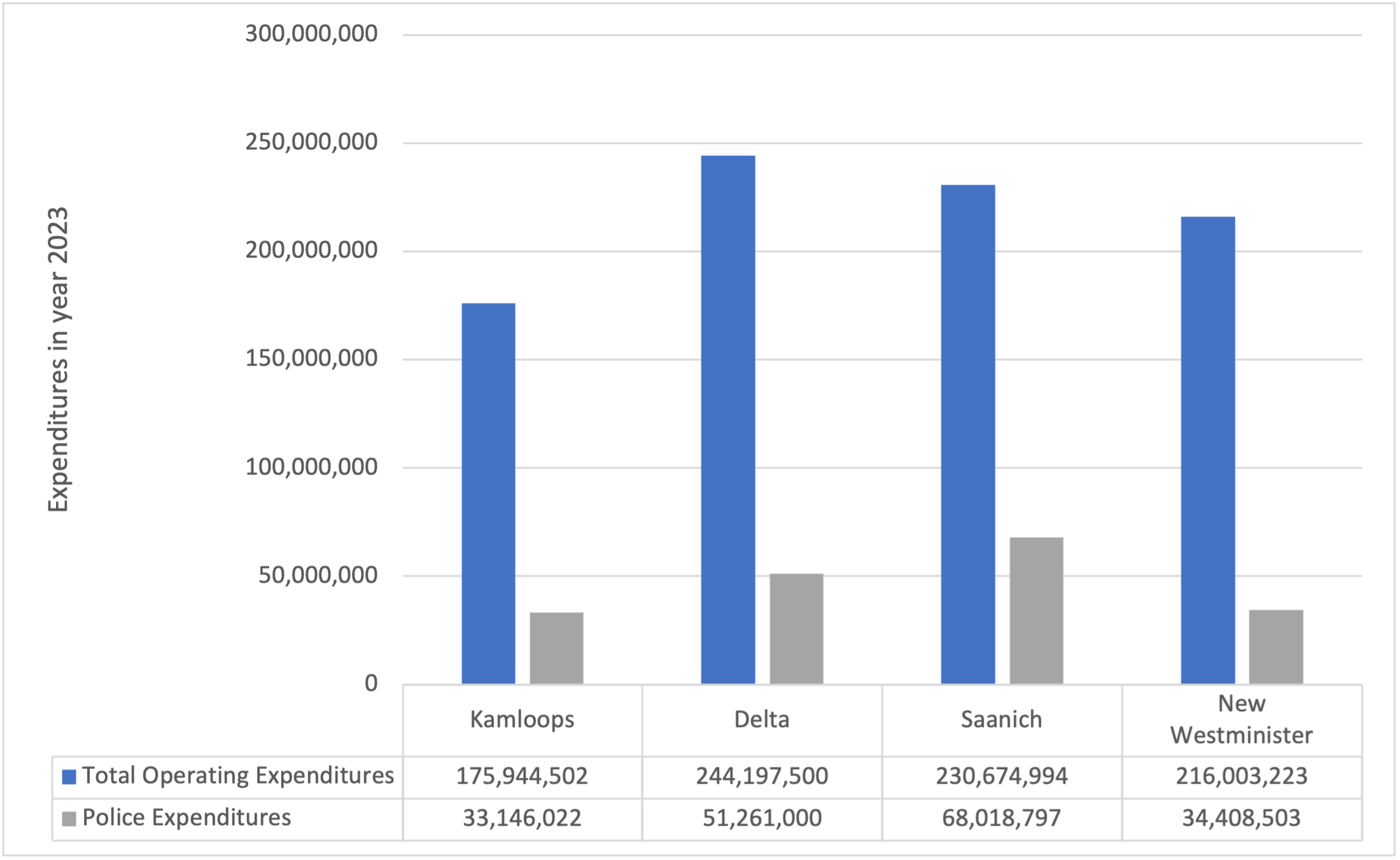

Currently, 12 municipalities in British Columbia have municipal policing services. For this chapter, we will compare the City of Delta, New Westminster, and Saanich; the two former are in British Columbia’s Lower Mainland, while the latter is on Vancouver Island. The municipality’s police board governs these municipal police departments. The role of the police board is to provide direction to the department under legislation and in response to the community’s needs (Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General Policing and Security Branch, 2023). Board members are civilians, and their departments are responsible for 100% of their policing costs (Government of British Columbia, 2021). Kamloops expenditures are ~18%, Delta’s are ~21%, Saanich’s are almost 30% of its total operating budget, and New Westminster’s are ~16%, the lowest of all four (see Figure 1).

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of each city being studied and compares it to the provinces of British Columbia and Canada. Comparing the population, median after-tax income, crime severity index, and the number of sworn officers. This table provides data that allows us to further analyze Kamloops compared to other cities and against the provincial or national averages. The Crime Severity Index (CSI) considers the volume and seriousness of crimes. In the calculation of the CSI, each offence is assigned a weight derived from average sentences handed down by criminal courts. All police-reported Criminal Code offences, including traffic offences and other federal statute offences, are included in the CSI.

Kamloops household median after-tax income for 2020 was $78,000, similar to the B.C. and Canadian average. Delta and Saanich have a higher household income than Kamloops, and New Westminster has the lowest household income at $72,500. Kamloops has the highest CSI amongst the four cities at 156.7. Next is New Westminster at 84.7, Delta at ~60, and Saanich, the lowest, at 51.3 CSI. Thus, the association, not causation, is that the municipal type of policing has a lower crime severity index relative to the RCMP type.

There are 689 people for each sworn officer in Kamloops, while Saanich has 714 people for each. Delta has 559 people for each sworn officer. A higher number suggests that each officer is responsible for a more significant segment of the population, which can impact response times, crime rates, community policing effectiveness, and the overall burden on the police force. Conversely, a lower number indicates a higher ratio of officers to civilians, which might imply better coverage and potentially more effective law enforcement. Hence, Delta has the best coverage, while Kamloops, Saanich and New Westminster might need more officers for potentially more effective coverage and enforcement. A similar indicator is the number of sworn officers per 1,000 people, but this time, a more significant number indicates a better coverage of 1,000 people (Delta).

Table 1: Crime & Policing in Kamloops vs. Other Places

| Skip Table 1 | |||||||

| City/Area | Population (2021 Census) | Median After-Tax Income of Households (2020) | Crime Severity Index (CSI) | Type | Sworn Officers | Population per Sworn Officer | Sworn Officers per 1,000 People |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kamloops | 97,902 | 78,000 | 156.70 | RCMP | 142 | 689 | 1.45 |

| Delta | 108,455 | 95,000 | 59.98 | MP | 194 | 559 | 1.79 |

| Saanich | 117,735 | 83,000 | 51.32 | MP | 165 | 714 | 1.40 |

| New Westminster | 78,916 | 72,500 | 84.73 | MP | 114 | 692 | 1.44 |

| British Columbia | 5,581,127 | 76,000 | 100.37 | MP/RCMP | 7,609 | 733 | 1.36 |

| Canada | 36,991,981 | 73,000 | 78.10 | MP/RCMP | 70,566 | 524 | 1.90 |

Note. Population data from Statistics Canada (2023b), Sworn officer’s data from the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General Policing and Security Branch (2023), Crime severity index from Statistics Canada (2023c), and Number of police officers in Canada from a Statista graph using Statistics Canada (2024) data.

Comparing RCMP and Municipal Police across Municipalities

Table 2 highlights that municipalities policed by the RCMP have much higher crime rates than municipalities policed by their municipal police force, regardless of population size. Although this may not be a cause-and-effect, municipal police are allocated to safer communities with a lower crime rate. Further studies will be needed to determine if there is a cause-and-effect. Future research should examine the city of Surrey as it transitions slowly from the RCMP to the municipal police system.

With a much higher crime rate in the municipalities policed by RCMP, there is also a higher workload per officer than that of the municipal police due to their lower crime rate. The RCMP-policed municipalities also suffer from a higher crime severity index (CSI). However, the RCMP has, on average, kept up with the population growth rate within British Columbia, whereas the municipal police have not. In the long run, this could cause some concerns as population density grows, and the ability to combat crime could become increasingly difficult without the appropriate resources for these municipal police forces. Additionally, it is essential to stress the benefits correlated to a higher cost per person to ensure a lower crime rate and CSI. This is further highlighted by Brand, Sam and Price, Richard (2000), Hassett, Shapiro (2012), and Welsh, Brandon & Farrington, David. (2018).

The cost per person in Table 2 represents the cost of servicing the police system in a community and does not include the true cost of crime. The cost of crime consists of the victim’s direct economic losses and intangible costs such as pain and suffering to the victim and family. Moreover, there are costs associated with operating the criminal justice system (i.e., policing, courts, prosecution, legal aid, correctional services) as well as the cost to society for someone pursuing a criminal career rather than pursuing a marketplace career (i.e., lost productivity, wages, and tax revenue). In Canada, the cost of crime is estimated at $100 billion. When including tangible and intangible costs to victims, the cost of operating the Canadian criminal justice system was estimated at $12.5 billion in 2014 and the cost of people pursuing a criminal career (MacKay, 2015). Given that in 2021, there were over 2 million police-reported Criminal Code incidents (excluding traffic) in Canada. The average cost per incident is estimated at $50,000 (Moreau & Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics, 2022).

Kamloops’ police expenditures in 2023 were estimated at $33.14 million (City of Kamloops, 2023a). The 2022 crime rate in Kamloops was 144 per 1,000 people, much higher than the averages shown in Table 2, and the caseload was 104 crimes per officer. Police expenditures in 2022 were $20 million lower than in 2023 at $31,14 million. Reducing the crime rate in Kamloops to 90 from 144 per 1000 people can yield significant benefits in terms of society costs avoided. This reduction is 54 fewer crimes per 1000 people or 5,400 fewer crimes in a city of 100,000 like Kamloops. Assuming it costs 50,000 per incident, the benefit of 5,400 fewer crimes is 270 million per year, or the benefits are five times more than the operating municipal cost of $51.26 million. If a transition to municipal police or a hybrid system can lower the crime rate, to say 50 per 1000 people, then the benefits would be 9,400 fewer crimes for a benefit of $470 million per year.

Table 2: Police and Crime Indicators Across Municipalities (Average)

| Skip Table 2 | |||||||

| Policing System Type | # of Municipalities | Crime Rate per 1000 People, 2022 | CSI, 2022 | Workload per Police Officer, 2022 | Cost per Person,2022 | Growth Rate of Police Officers, 2013-2022 | Population Growth Rate, 2011-2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCMP Population 15,000 & Over | 32 | 94 | 111 | 73 | 281 | 17 | 19 |

| RCMP Population Less Than 15,000 | 35 | 92 | 110 | 63 | 240 | 11 | 10 |

| Municipal Police | 11 | 51 | 70 | 32 | 386 | 4 | 9 |

Note. Data from Statistics Canada (2023a, 2023c) and the Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General Policing and Security Branch (2023)

Examining the costs of crime allows for comparing the comparative burden of different crimes on society. Information on the costs of crime, the cost of policies designed to reduce crime, and the effectiveness of various policies can be used in resource allocation decisions. Ultimately, the bottom-line question is: Which programs and policy options will yield the most significant reductions in crime at the lowest cost? Some crime prevention programs, for example, have produced reductions in crime, criminal justice, and mental health costs that are many times the amounts invested. It has been estimated that the cost per crime incident is over one million dollars.

Police Interviews

RCMP Officer

The interview with the RCMP officer from Kamloops highlighted several key issues facing the force as it adapts to growing population demands and evolving crime trends (RCMP Officer, personal communication, April 1, 2024).

Challenges — Funding

The officer emphasized the consistent need for more resources, particularly staffing, to enhance their presence and response times in the community. Despite increased resources over the past six years, the officer felt it was still insufficient to meet demands. On average, only about 14 officers are available daily, contingent on total attendance.

The Car 40 mental health program, pairing officers with mental health nurses, is praised but limited by the capacity to staff one nurse at a time, pointing again to funding constraints (RCMP Officer, personal communication, April 1, 2024). The officer suggested that more effective change could be realized with better budget allocation.

Challenges — Lack of Police Resources

Since 2012, Kamloops has seen quite a bit of growth, with the population growing from 88,523 to an estimated 108,551 in 2024 (Statistics Canada, 2023b). The RCMP has also seen a reasonable amount from 2013–2022 of growth from 124 to 142 sworn-in officers (Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General Policing and Security Branch, 2023). These statistics provided in the interview show that while Kamloops’ population has grown by 22.6% from 2012 to 2024, the number of sworn officers has only increased by 14.5% from 2013 to 2022, indicating a lag in police force growth compared to population growth. This discrepancy suggests a need for a significant increase in police resources to keep pace with demographic changes. “Having a presence makes the biggest difference,” said the RCMP officer when asked about effective methods of preventing crime (RCMP Officer, personal communication, April 1, 2024).

Challenges — Recruitment

Additionally, the officer touched on challenges in recruitment, citing a negative stigma towards policing as a barrier, and outlined efforts to engage youth through informational sessions and educational programs (RCMP Officer, personal communication, April 1, 2024). The RCMP officer noted that “during the March break camp for high school students, they are eligible to earn a credit for completion of the camp put on by the RCMP.” Finally, the officer noted that the RCMP does do monthly reports that are presented to the city council members and the mayor, which could impact resource allocation and operational effectiveness. However, unlike the municipal police, the RCMP does not have the same vested interest from the city as they are contracted out and not the city’s entity.

Municipal Police Officer

The interview with a municipal police officer from B.C.’s Lower Mainland shed light on municipal policing, emphasizing its strengths and the obstacles it faces today (Municipal Police [MP] Officer, personal communication, April 3, 2024).

Advantage — Local Control Over Police Forces

One significant advantage of municipal policing is the greater control local authorities have over their police forces. This direct oversight allows for more targeted responses to specific community needs supported by a commitment from mayors and councils who directly oversee and invest in police infrastructure, personnel, and resources, including equipment, buildings, staff, logistics, and vehicles. This model supports a philosophy deeply rooted in the idea that officers and the community they serve are inherently linked, enhancing mutual respect and cooperation for public safety. The municipal officer stated the following principle, “The police are the people, and the people are the police.” Having civilians turn into sworn officers from within their community continues to amplify that vested interest in the betterment of their community.

Advantage — Active in Communities

What makes municipal policing models so effective? First and foremost, they try to be proactive by being highly active in communities. “During peak crime times, typically the evening, boots on the ground in trending areas are key to being proactive at policing or eradicating crime,” the municipal officer stated (MP Officer, personal communication, April 3, 2024). While the officer interviewed could not speak to what makes New Westminster or Saanich so effective, the officer again mentioned that Delta’s Police Department is known for having exceptional community relationships. In the city of Delta, their police force has an exceptionally good reputation. However, the officer also outlined several significant challenges. Like the RCMP, one of the biggest challenges is managing the cost budget, as emergency services share many of the costs. Municipalities rely heavily on local taxation without substantial federal or provincial support.

Challenges — Staffing

Another challenge municipal forces face is staffing. Questions are raised about how to connect to this generation of workforce. The officer again highlighted that “following the pandemic, a lot of people want to have work-from-home jobs or highly flexible schedules, which is challenging to attract” (MP Officer, personal communication, April 3, 2024). Attracting recruits in a post-pandemic world, where potential candidates often seek jobs with remote work possibilities and flexible schedules, is a critical issue for policing as they cannot typically offer these options. Additionally, there is an ongoing need for specialized staff, such as crime analysts, who play a crucial role in assessing crime patterns and helping to allocate resources more effectively.

Challenges — Training

The officer also highlighted the high costs of training recruits (MP Officer, personal communication, April 3, 2024). As tuition fees continue to rise, there is a push towards more sustainable and cost-effective training models. Currently, municipal police forces train out of the Justice Institute in New Westminster, which comes at a considerable cost to departments. In December 2022, an email from Superintendent Jennifer Keyes, Director of the Police Academy, sent an email to Chief Constable Dave Jansen of the New Westminster Police Department stating that the tuition cost for training a recruit would go up 5% from $22,110 to $23,215, effective April 1, 2023.

One proposed solution is for municipal police departments to develop training programs that could be tailored more closely to their specific needs and potentially be less costly than current centralized training systems. However, it could be challenging to fund such initiatives with a lack of government funding other than provincial or city taxes. There may also be a lack of community support. This municipal officer believes that their model is the preferred method of policing due to having access to better equipment, better resources, and better-quality officers who are highly selected and trained (personal communication, April 3, 2024). Other municipal police departments opt for the Justice Institute of British Columbia’s nine-month training program versus the RCMP’s six-month militaristic style of training at their depot facility. In addition, this officer has witnessed many surveys conducted through their department that conclude that people have more of a personal connection to municipal officers than RCMP.

Suggestions for the Future

Toward the end of our interview, this municipal officer with over 20 years of experience left a few suggestions for the future. Different municipalities could share the financial burden and logistical responsibilities by regionalizing resources, fostering a more robust and economically viable policing network across regions. This could include shared emergency response teams and potentially integrating services like transit police into a broader cooperative framework. These strategies, while ambitious, could significantly enhance the efficacy and sustainability of municipal policing in adapting to the evolving demands of public safety.

Table 3 summarizes information provided by both police officers interviewed for the study.

Table 3: Interview With RCMP vs Municipal Police

| Skip Table 3 | ||

| Aspect | RCMP Interview (Kamloops) | Municipal Police Interview |

|---|---|---|

| Funding & Resources | There is a constant need for more resources, especially staffing; funding is insufficient despite increases; one mental health nurse in Car 40. | Better equipment and resources due to local control and investment; high costs for training recruits. Proposed to develop their training programs due to high costs associated with centralized training. |

| Growth vs. Needs | Population has grown 22.6% since 2012, while officer numbers only grew by 14.5% from 2013–2022, suggesting a lag in force growth. | Emphasis on the ability of local governance to tailor resources effectively to community needs. |

| Community Relationship | The Car 40 program was praised; the city council’s lack of sufficient community investment could affect operational effectiveness. | Strong community relationships are highlighted, emphasizing mutual respect and cooperation. The public feels a personal connection with municipal officers. |

| Recruitment Challenges | Recruitment challenges due to negative stigma; efforts to engage youth through educational programs. | Challenges in attracting recruits post-pandemic who seek flexible work arrangements. High costs of training and need for specialized staff like Crime Analysts. |

| Training | 26-week Cadet Training Program at Depot in Regina, Saskatchewan. | Uses the Justice Institute for a 9-month training period, viewed as better quality than RCMP’s shorter, militaristic style. |

| Strategic Approaches | Emphasis on the need for better budget allocation. Active during peak crime times, i.e., downtown nighttime. It is tough to accomplish with limited resources. | Proactive policing during peak crime times; suggestion for regionalization to share costs and resources. |

| Advantages | Mention of a mental health collaboration program. Shift pickup at different detachments. Flexibility to move around Canada. | Greater control over policing by local authorities allows for more targeted responses; local taxation supports direct investments. |

| Suggested Improvements | Better budget allocation to meet community demands. More staff allocated by RCMP. | Development of local training programs; regionalization of resources for economic viability. |

Note. Data was compiled from interviews with an RCMP Officer (personal communication, April 1st, 2024) and a Municipal Police Officer (personal communication, April 3rd, 2024).

The Role of AI and Robotics in Policing

As technology continues to evolve, integrating artificial intelligence (AI) and robotic tools into policing could provide Kamloops with new opportunities to enhance law enforcement efficiency. AI-driven predictive policing can analyze crime patterns and allocate resources more effectively, helping prevent incidents before they occur. Additionally, AI-assisted surveillance tools, including automated license plate recognition and facial recognition software, can improve investigative capabilities.

Robotic technologies, such as drones and autonomous vehicles, could assist in search-and-rescue operations, monitoring public spaces, and reducing risks for officers in hazardous situations. AI-powered chatbots and reporting systems could streamline non-emergency communications, reducing administrative burdens on police departments.

However, integrating AI and robotics into policing also presents challenges. Ethical concerns regarding data privacy, potential biases in AI algorithms, and the need for public trust in automated decision-making must be addressed. Furthermore, implementing these technologies requires significant investment, training, and regulatory oversight to ensure they are used responsibly and effectively. If Kamloops moves toward a more technologically advanced policing system, careful planning and public consultation will be necessary to balance innovation with community expectations.

Ultimately, the future of policing is dynamic and constantly adapting to the needs of cities in British Columbia and Canada. As the country grows so quickly and areas like B.C.’s Lower Mainland become denser, the possibility of regionalizing police is not far away. It would allow for combined resources and integration where needed and make police more efficient at combatting or being present in crime hot spots in different communities. This is not to slight the current RCMP in Kamloops, but being tied to such a decentralized government means they are at the mercy of a widespread budget and limited resources. The answer to a limited budget for Kamloops policing could be to regionalize itself in the Thompson-Nicola Police Service (or just known as the Kamloops Police Department), serving the communities of the Thompson-Nicola region, including Kamloops, Merritt, Chase, Clearwater, Logan Lake, Barriere, Ashcroft, Cache Creek, Clinton, Sun Peaks, and Lytton.

While there are the initial upfront costs of establishing a newly formed police department, a Thompson-Nicola police force could tie together methods used by the Surrey Police Service, which is currently transitioning from the RCMP to its city police. According to Solicitor General Mike Farnworth, in July of 2023, Surrey’s decision was made after the RCMP faced critical staffing shortages. He also stated that keeping Surrey on track for this transition was the “right thing for the people of Surrey and across our province (Meissner, 2023). Additionally, a report from his office is said to have 842 RCMP members leaving or retiring and 638 recruits nationwide, while there are currently about 1,500 vacancies across the RCMP in B.C.

It is found that there is a correlation between having a lower socioeconomic status and crime rates. Higher population densities and specific land use patterns may increase the opportunity for crime; adding in the increasing homeless population in Kamloops only adds fuel to the fire. A Kitchen (2007) study for the Department of Justice Canada concluded that the geography of crime can also be expected to vary considerably, not only within cities but also between cities. Fully accounting for these differences is needed to develop appropriate strategies for crime prevention and social upgrading that deal specifically with local circumstances.

Therefore, as Kamloops and the Thompson-Nicola continue to combat the crime rate shorthandedly, it is time for the region to come together and address the rising crime rate and lack of resources. A Kamloops or Thompson-Nicola police service could be the answer to pulling together all funding available and starting to prevent crime rather than react to it with an insufficiently funded RCMP detachment. This solution may work if Canada’s government needs help finding a better way to staff and fund the RCMP in addition to the funding already provided by the city of Kamloops. Many questions need to be asked about how to improve the efficiency of the city’s current policing model and how they can attract more people to the job.

Media Attributions

Figure 1: “Total operating expenditures by each city as well as their police expenditures in CAD bar graph” [data source] by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

Figure 2: “Patrick Izett’s poster presentation at the 19th TRU undergraduate conference in March 2024” by the author is under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

BC Stats. (2023, October 1). Quarterly population highlights. Government of British Columbia. Retrieved January 23, 2024, from https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/data/statistics/people-population-community/population/quarterly_population_highlights.pdf

Brand, Sam and Price, Richard (2000): The economic and social costs of crime. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/74968/

City of Delta. (2023). 2023 Financial Plan. https://www.delta.ca/sites/default/files/2023-01/2023%20Financial%20Plan.pdf

City of Kamloops. (2023a). City of Kamloops: Statement of financial information for year ended December 31, 2022. https://www.kamloops.ca/sites/default/files/2023-07/City%20of%20Kamloops_2022%20SOFI%20Attachment%20A.pdf

City of Kamloops. (2023b). Financial plan 2022-2026. https://www.kamloops.ca/sites/default/files/docs/Financial%20Plan%202022-2026%20-%20FINAL%20-%20Combined_web.pdf

City of Vancouver. (2022). Vancouver budget 2022 and five-year financial plan. https://vancouver.ca/files/cov/2022-budget-document-consolidated.PDF

Corporation of the City of New Westminster (2023). 2022 Statement of financial information. https://www.newwestcity.ca/database/files/library/2022_Statement_of_Financial_Information.pdf

Corporation of the District of Saanich. (2023). 2022 Statement of financial information. https://www.saanich.ca/assets/Local~Government/Documents/Corporate~and~Annual~Reports/Saanich%20SOFI%202022.pdf

Cyr, K., Ricciardelli, R., & Spencer, D. (2020). Militarization of police: A comparison of police paramilitary units in Canadian and the United States. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 22(2), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461355719898204

Demers, S. (2019). More Canadian police means less crime. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 61(4), 69–100. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2018-0049

Goldstein, R., Sances, M. W., & You, H. Y. (2018). Exploitative revenues, law enforcement, and the quality of government service. Urban Affairs Review, 56(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087418791775

Government of British Columbia. (2021, March 5). Municipal policing. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/justice/criminal-justice/policing-in-bc/the-structure-of-police-services-in-bc/municipal

Griffiths, C. T. (2019). Policing and community safety in northern Canadian communities: challenges and opportunities for crime prevention. Crime Prevention and Community Safety, 21, 246–266. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-019-00069-3

Griffiths, C. T., Murphy, J. J., & Snow, S. R. (2014) Economics of Policing: Baseline for Policing Research in Canada (Catalogue No. PS14-30/2014E-PDF). Public Safety Canada. https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/bsln-plcng-rsrch/bsln-plcng-rsrch-en.pdf

Hasset., R. Shapiro., (June 2012). A case study of 8 American cities. The Economic Benefits of reducing violent crime. https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2012/06/violent_crime.pdf

Kitchen, P. (2007). Exploring the link between crime and socio-economic status in Ottawa and Saskatoon: A small-area geographical analysis. Department of Justice Canada, Research an Statistics Division. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/csj-sjc/crime/rr06_6/rr06_6.pdf

MacKay, P. (2015). The costs of crime in Canada. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2015/04/costs-crime-canada.html

McIntosh C, & Li, J (2012) An Introduction to Economic Analysis in Crime Prevention: The Why, How and So What, Research Report: 2012-5, National Crime Prevention Centre (NCPC), Public Safety Canada, Ottawa, Ontario Canada, https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/cnmc-nlss/index-en.aspx

Meissner, D. (2023, July 19). Province orders City of Surrey to stick with transition to municipal police force. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/surrey-police-service-rcmp-transition-bc-decision-1.6910870

Ministry of Public Safety an Solicitor General Policing and Security Branch. (2023). Police resources in British Columbia, 2022. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/law-crime-and-justice/criminal-justice/police/publications/statistics/bc-police-resources-2022.pdf

Moreau, G., & Canadian Centre for Justice and Community Safety Statistics. (2022). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2021 (Cat. no. 85-002-X). Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/85-002-x/2022001/article/00013-eng.htm

Murphy, C. (1998). Policing postmodern Canada. Canadian Journal of Law and Society, 13(2), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S082932010000572X

Police Act, RSBC 1996, c. 367. https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96367_01

Policing and Security Branch, Ministry of Public Safety and Solicitor General, Prepared December 2023, B.C. Police Resources 2022 (gov.bc.ca)

Slotwinski, M. (2010). Law enforcement expenditures and crime rates in Canadian municipalities: A statistical analysis of how law enforcement expenditures impact municipal crime rates in Canada. MPA Major Research Papers, Article No. 89. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/lgp-mrps/89

Statistics Canada [Prepared by BC Stats]. (2023a). British Columbia municipal census populations 1921 to 2021 [Table]. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/data/statistics/people-population-community/population/municipal_census_pop_1921_2021.pdf

Statistics Canada. (2023b). Census profile, 2021 census of population (No. 98-316-X2021001) [Table]. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E

Statistics Canada. (2023c). Crime severity index and weighted clearance rates, police services in British Columbia (No. 35-10-0063-01) [Table]. Government of Canada. https://doi.org/10.25318/3510006301-eng

Statistics Canada. (2024). Number of police officers in Canada from 2000 to 2003 [Graph]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/436274/number-of-police-officers-in-canada/

Stelkia, K. (2020). An exploratory study on police oversight in British Columbia: The dynamics of accountability for Royal Canadian mounted police and municipal police. Sage Open, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019899088

Sytsma, V., & Laming, E. (2019). Exploring barriers to researching the economics of municipal policing. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 61(1), 15–40. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2017-0056.r2

Welsh, Brandon & Farrington, David. (2018). Assessing the Economic Costs and Benefits of Crime Prevention. DOI. 10.4324/9780429501265-1. https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/edit/10.4324/9780429501265/costs-benefits-preventing-crime-brandon-welsh

Long Descriptions

Figure 1 Long Description: The bar graph displays the total expenditures for the following cities:

- Kamloops

- Total operating expenditures — 175,944,502

- Police expenditures — 33,146,022

- Delta

- Total operating expenditures — 244,197,500

- Police expenditures — 51,261,00

- Saanich

- Total operating expenditures — 230,674,994

- Police expenditures — 68,018,797

- New Westminster

- Total operating expenditures — 216,003,223

- Police expenditures — 34,408,503